The integrated project delivery (IPD) model has been around for close to two decades and, while it began in the United States, it’s slowly picking up speed in Canada. In fact, IPD has been called one of the future trends that will impact the construction industry.

According to the Canadian-based, Integrated Project Delivery Alliance (IPDA), there are currently 50 projects either complete or in progress right now, not including ones that are in procurement.

From start to finish, an integrated project differs from a traditional one.

For example, design decisions are moved to the beginning phases of a project—where they can be more effective and less costly. In doing this—and implementing early team engagement—the project has a higher level of completion prior to pre-construction, reducing time and increasing savings.

By optimizing early engagement from all stakeholders—trade partners, architects, owners, and contractors—IPD creates a much deeper level of collaboration. It naturally fosters efficiency, innovation and goal alignment.

During a recent INFRAIntelligence webinar, ReNew Canada, with support from Graham, discussed with a panel of experts what’s driving IPD and how infrastructure project finance and procurement is changing in other ways. How have delivery models evolved over the years? What have we learned from past projects and where are the opportunities in the future?

IPD adoption

The business case for IPD from an owner’s perspective is that it is supposed to optimize the project constraints of cost, time, quality, and other risks. Proponents of IPD believe that in other traditional project delivery models (e.g., design-bid-build or design-build) the optimization of these constraints comes at the sacrifice of others. From the perspective of other project parties like design professionals, contractors and trades, IPD is aimed at increasing efficiency, reducing waste and minimizing disputes.

According to Neal Panchuk, pre-construction manager with Graham’s Toronto buildings team, the increasing complexity of projects has owners looking for alternative delivery models.

“The old way of working, where we’re throwing information over the fence from one consultant to another and back to the contractor for pricing, has proved time and again that that’s failing. And that’s where IPD comes in and allows us to get out of the gate in an aligned manner right from the start.”

It’s not necessarily just about adoption of the IPD model, says Mark Van Buren, deputy commissioner of major projects, for the City of Kingston, who is currently leading a small team of city staff that are integrated with a design team from Hatch and Systra and a construction team from Kiewit, who are working on the planning, design, and construction of the Third Crossing bridge project.

“I’m not so sure about the adoption at this point, but I’d say the interest is enormous,” he explains. “I get inquiries, almost on a weekly basis, about what’s going on in Kingston and ‘I’d like to learn more about what you guys are doing for IPD.’

“And from an owner’s perspective, I think there’s a point of getting tired where you constantly are dealing with projects that are missing budget, missing schedule, and you don’t have the constant looming threat of legal action between the parties. And [IPD] really set the table for how we can do things differently.”

But not every project is right for IPD, says Louise Panneton, president of P1 Consulting.

“Some of the clients we work with, for example large government entities, have the bulk of their project that should be developed through design-bid-build, or design-build.”

At its core, a successful IPD project is about selecting the right team—all team members need to be able to communicate and collaborate and be capable of working in new ways that require new skills. The team also needs to align with the initial project objectives and be invested in a successful outcome.

In her experience, Panneton says there are two tests to determine where the IPD model should be used.

- Do you have the right team?

“As we start looking at projects, will you have the right people at the table to actually carry this project through and have the right attitude?”

- Do you have the right governance?

“In the approval process, have you figured out how to move your project through the entire approval process and do you have the approval and endorsement from the executive team?”

Bringing everybody to the table up front is a big benefit to IPD, adds Dick Bayer, vice president with Colliers Project Leaders’ IPD and Lean services team.

“We get to know an awful lot earlier on things we just used to make assumptions on. So, the more we know earlier, the better we are, and that is right at the top of risk management.”

Collaborative management of risk, identification of risk, these are important benefits of IPD and, according to Panneton, owners are starting to really rally behind that.

From the perspective of everyone involved in an IPD project—the owner, the consultant, the contractor—they all want certainty, adds Van Buren.

“And in that journey, you look at risk. Every party is trying to minimize their risk. And I think the evolution that we have seen is that we’ve gone from constantly trying to monetize that risk and then trade it away to flipping that around and saying, ‘Well, why don’t we actually try to embrace that risk or share that risk?” And I think that’s the heart of what IPD tries to do, is to take that shared risk, shared reward approach.”

Breaking old habits

The challenges that typically face IPD projects can include higher upfront costs for the owner during the validation and pre-construction phases, difficulty for consultants and trade partners to adapt to this new model and way of thinking, difficulty creating an open and collaborative environment among the various players, and a greater time commitment.

People can be the most important factor, says Panneton.

“This is all about people. If you have the right people around the table, your project will be amazing.”

Keeping changes to a minimum is another key to a successful outcome, as IPD is not designed to have a very significant number of changes, adds Panneton. “[IPD] is designed to have a good solid outcome and collaborative work to get there. So, if you don’t know what your project is, it’s probably not a good candidate for IPD.”

Another obstacle can be the inherent transparency of the IPD model—the notion of people being comfortable with the idea that consultants and contractors make profit and understanding what exactly that profit is—says Van Buren.

“In some circles, that makes people feel uncomfortable to be having those discussions with our public, with our residents. These are things that in other models we’ve always kind of obscured or we don’t talk about it.

“But [IPD] is very transparent and very open. And that’s a little bit of a shift in the conversation to be having. It is all about people and breaking old habits and being open to different approaches.”

As with anything new, it’s really a behavior change on everybody’s part, adds Panchuk.

“There can be no egos in IPD. You have to drop your ego at the door and say, ‘We’ve developed our conditions of satisfaction and values and that’s what’s driving us.’ It’s not the loudest voice in the room.”

Using cost as an input to design is one of the biggest challenges with IPD, according to Bayer.

“That’s a really difficult thing to do. Getting designers, who are so used to designing and pricing, to have a really robust estimator at their side or an estimation desk in the room, where they can get information about cost is a cultural change that’s always a difficult challenge.”

Money issues

With the City of Kingston’s Third Crossing bridge project, based on the city’s review of procurement alternatives and benefits during the business case phase, the innovation of an IPD model stood above other options because it allows for the technical validation, detailed and final design, and construction to be seamlessly wrapped into one project model using a less adversarial contract and delivery approach.

For Van Buren, one of the important ingredients was the extent to which the owner is involved.

“It was one of the points of consideration that we had in discussions with our city council around what was going to be the most suitable procurement model for our project. It was about not diminishing the value that we as the owner could bring to the discussion.”

From the other side of the table, it’s about trying not to make decisions in the absence of input from the owner simply because it’s not your money, says Panchuk, it’s the stakeholders’ money.

That’s when the benefits of getting advisors in early to help educate owners prior to getting an RFP become apparent, “So they can quantify in their brain, ‘what am I actually looking for as an end state.’ Because we’re not mind readers, we can’t provide that for you,” he says.

“You need to help us determine what value is, and we can collectively move forward.”

When it comes to the evolution of IPD and how to improve the model, Van Buren, for one, thinks there is an opportunity to build on the current level of collaboration between project owners and their partners by creating an environment where regulatory bodies can be brought to the table to really capitalize on efficiencies.

“And maybe that’s the journey ahead as we think creatively about how we can do that.”

[This article originally appeared in the March/April 2022 edition of ReNew Canada.]

John Tenpenny is the editor of ReNew Canada.

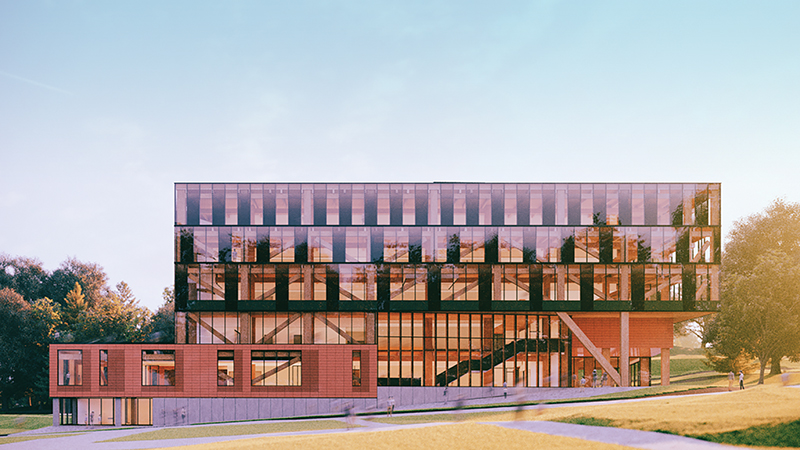

Featured image: The City of Kingston, using IPD, is integrated with design and construction teams that are working on the planning, design and construction of the Third Crossing project. (City of Kingston)