Large-scale infrastructure projects from procurement to completion are becoming increasingly complicated and risky in Canada. Local opposition, and the political response it inevitably generates, has become the norm when considering how best to advance infrastructure programs. In the past, opposition was often fragmented, with disjointed arguments. However, the advent of social media has made “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) interests much more organized and highly effective politically.

One just has to look at what happened in Ontario with the Mississauga and Oakville gas plants to recognize that the public procurement landscape is shifting as a result of these better-organized campaigns and social media. Across Canada, large and desperately needed infrastructure projects have been subject to multiple delays and reconfigurations due to political interference, often generated by local activists. In some cases, this local opposition is augmented by support from larger special-interest groups, such as environmental NGOs, who have become adept at working with local communities to block or delay projects.

In this climate, politicians are much less willing to expend the political capital when pressure mounts on infrastructure projects. The relatively short electoral cycle, and the multiple layers of government providing funding, creates multiple points of project vulnerability. Changes in government can also bring different ideas for what a project should ultimately look like, with politicians wanting to either put their own stamp on a project or live up to promises made during election campaigns.

Infrastructure procurement works best when the party most able to assume the risk does so. For example, the risk related to cost overruns and project delays are best borne by the private sector, whereas policy and political risk is best borne by the government. This clear division of risk is especially important with large-scale infrastructure projects.

With an increasing number of projects being rolled out using public private partnerships, this has further weakened the political resolve to defend projects once a contract is signed. Once the financial and project delay risks are handed over to the private sector, the government seemingly now also expects the private sector to assume the policy and political risks associated with projects the government itself is procuring.

Given the massive amounts of investment required to bring these mega-projects to fruition, are we now likely to see private-sector partners forced to incorporate policy and political risk into their project pricing? In light of such a possibility, there are measures that can be taken within the procurement process and during the construction phase to help mitigate the impacts of this trend of policy and political risk transfer to the private sector.

Ensuring transparency

Large infrastructure procurements in Canada often need the financial support of municipal, provincial, and federal levels of government. Transparency is provided through such devices as public project agreements and value-for-money reports. Although these documents are useful for displaying the transparency of project decisions on a financial basis, they do little in terms of ensuring transparency between bidders and the government on a transactional basis throughout the procurement process.

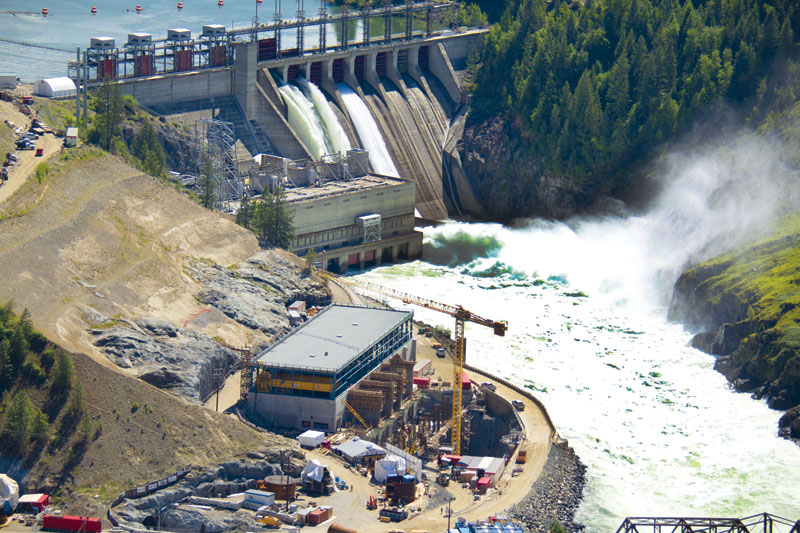

As mega-projects are being proposed across the country—from the massive transit projects in the Greater Toronto Area to the large hydroelectric projects in British Columbia and Quebec—this type of transactional transparency is critical to project success and to mitigating the policy and political risk mentioned earlier. In Europe, rules set down by the European Union have forced a higher level of transparency of procurement processes across the continent, with a view to bringing more openness and fairness to national procurement markets. With the recent signing of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the European Union and Canada, we are undoubtedly moving in the same direction.

Such transparency has meant that any decisions must be justifiable and defensible. Although the system is not perfect in Europe, it is improving the infrastructure landscape on a number of levels. More transparency brings greater competition in procurements, as bidders know they will be fairly treated, leading to greater value for money for taxpayers. By requiring authorities to provide justification for why a particular decision was made, it has shown losing bidders where they need to improve in order to be successful, creating a virtuous cycle. Finally, it has imposed a discipline on public-sector buyers, which has reverberated up through public infrastructure projects, making the procurement framework more robust, and providing a strong basis for sound project management from an early stage.

This new discipline is starting to bear fruit on large infrastructure projects in Europe, where together with the rollout of different procurement and financing models, it has contributed to a reduction in frequency of the spiralling budgets and major delays that were once the hallmark of major infrastructure projects. One example is Crossrail (see “Light at the End of the Tunnel” at bit.ly/crossrailrc), a £16 billion underground rail link running under central London, and the largest infrastructure project in Europe. Crossrail has so far achieved that rarest of feats for a mega-project in managing to stay on time and on budget. Although the project is only at the halfway stage, this still represents some achievement, and spurred the announcement of Crossrail 2.

Having a strong foundation for the project through better-constructed procurements, and compiling the information to make any decisions easier to defend, reduces the temptation for political interference. But the private sector must also step up to mitigate risk around projects. Political risk is being handled in a de facto manner by the private sector. In some cases, lawsuits and massive settlements have been the result.

Fostering good communication

To start, better communication from the companies managing major infrastructure projects around the awarding of subcontracts would be beneficial. Smaller local subcontractors see these large projects as major opportunities that may not come around very often. Here in Ontario, we have seen examples of small local companies, frustrated at losing out on contracts on major projects, making that frustration clear to their local politicians. This causes a rise in friction between local political representatives and the project leads. It can also lead to an erosion of trust with the local community and increases the temptation for the government to get involved.

Establishing strong lines of communication and a relationship is critical. Politicians, policy makers, private sector companies, and the public need a way to see why and how a specific company or consortium won the work and how they are delivering for the community. Included in this is why the project is necessary in the first place and why the proposed solution is the right one. This type of dialogue needs to be continued throughout the duration of the project to ensure communication between the government and the private sector, and to ensure both are provided with up-to-date and defensible project information.

Too often, relationships between political leaders and the project leads only develop when things start going wrong. It then becomes very difficult to build any level of trust, or get across the necessary complexities of project to enable politicians to make informed judgments. The risk then is that political leaders find themselves on the back foot as the media and political opponents start to get involved. They must be seen to act swiftly in holding those deemed responsible to account in the eyes of the public.

For our much-needed, larger-scale infrastructure projects to succeed, we need to ensure risk remains appropriately assigned and that protections are built in to buttress against inappropriate, albeit unintentional, risk transfers to either sector. Politicians need to know that proponents have the ability to deliver projects on time and on budget; proponents need to know procured projects will be seen through to completion and operation; and stakeholders need to have faith that a fair and transparent procurement has been conducted and will be defended by the government and its private-sector partners.

Stable, well-managed projects create confidence and give political leaders and the taxpayer the desire to commit to investing in more projects. It is time for Canada to move forward on procurement reform and implement a system that will encourage large-scale development. With massive projects already underway across Canada, there is no better time than the present to start this process. Provinces and municipalities across the country are putting more emphasis, and more funding into infrastructure development than ever before. The question remains are politicians willing to rebalance the system and accept their share of risk that they have recently shed?

David Caplan is the vice-chair of Global Public Affairs.