Buildings represent approximately 30 to 40 per cent of total worldwide energy consumption, and they are a major component of the public-sector carbon-emissions footprint. In fact, at a recent welcome address to a conference in Chicago, the sustainability director for the host city broke down its carbon emissions: one per cent for water and wastewater; five per cent for waste and recycling; 23 per cent for transportation; and 71 per cent for city buildings.

In May 2013, worldwide carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere hit a symbolic benchmark, reaching 400 parts per million for the first time in three to five million years. This dubious honour highlights the importance of the public sector’s role in both leading the actual reduction and leading by example. In this effort, it is also clear that much of the carbon emissions for public-sector organizations are related to energy consumption in their buildings and infrastructure.

There has been leadership in promoting greener, more environmentally friendly construction processes, but the energy and carbon footprint for constructing a building is miniscule compared to that of a building’s entire life cycle. It is expected that 75 per cent of existing buildings will still be part of the building landscape 30 years from now, and for the public sector—whose infrastructure is designed to last much longer than its commercial counterparts—this is especially true. Thankfully, there are still significant opportunities for real energy, greenhouse gas (GHG), and cost savings from existing public-sector buildings. However, the challenges—and responses—are changing.

It stands to reason we must begin to measure how we operate our buildings and manage their performance more tightly, as increasing the visibility of actions to reduce energy costs and consumption helps to draw support and build momentum. In Canada, the growing popularity of the BOMA BESt and LEED for Existing Buildings: Operations and Maintenance green building rating systems promote efficiency, as higher energy performance is key to achieving higher rating levels within both systems.

Energy is also becoming more visible with benchmarking and ranking tools like the Canada Green Building Council’s GreenUp national benchmarking program and Natural Resources Canada’s efforts to introduce Energy Star Portfolio Manager for Canadian offices and schools.

A further scan of the global marketplace shows even more targeted, and sometimes legislated, reporting on energy performance of buildings.

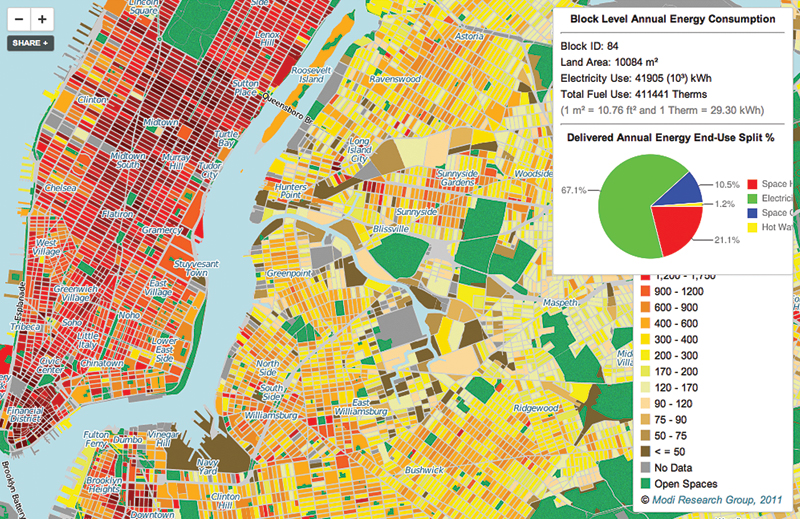

The plaNYC 2030 program in New York City aims to reduce emissions by 30 per cent by 2030; it requires the annual public posting of the energy use intensity, the Energy Star rating, and water use for all public buildings in excess of 10,000 square feet and all private buildings larger than 50,000 square feet. Consequently, this annual report has created a visibility for energy that’s starting to influence the market and public building managers. The Columbia Engineering School had already created an interactive map showing energy consumption at the lot scale, based on statistical analysis; the recent release of New York’s database at the building scale in a similar form is inevitable, providing an unparalleled market view to building occupants, lessors, buyers, sellers—and ratepayers.

Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Seattle, Austin, Chicago, and Philadelphia, and states like California, Alaska, Kansas, and South Dakota, now have similar building energy regulations for commercial buildings. Boston, Portland, Minneapolis, Denver, Illinois, and Maryland are piloting or drafting labelling policies and programs intended to make building energy consumption transparent and accessible.

This rapidly growing movement has been learning from European Union legislation that requires building energy disclosure for both new and existing buildings. Legislation in the United Kingdom takes these requirements to the next level: it requires all buildings to have Display Energy Certificates (DEC).

Real-time displays of energy metrics and goals are another emerging trend now being used in many buildings around the world to inspire engagement among operating staff and building occupants. LCD screens in lobbies and elevators, and smartphone communications convey energy-performance information, engendering accountability and cooperation toward a common goal of improving sustainability through reduction of energy consumption.

Natural Resources Canada introduced its national framework for building energy and emissions labels in June 2013. Canadianizing the U.S.’s Energy Star Portfolio Manager framework will provide a common language for building energy and GHG performance across North America. Initially for offices and schools, it will establish a protocol for utilities and local governments to merge energy and ownership datasets, reducing reporting costs, and will become a common metric for building energy management.

To date, green-building labelling programs have recognized the better performing buildings. Broader building energy benchmarking and public disclosure will inevitably highlight poor performers. As energy performance becomes publicly available, inevitably, questions will arise from those paying the bills. As public benchmarking makes building energy performance more transparent, pressures will grow on public sector portfolio and building managers to improve performance, lead by example, and continuously improve. A growing body of evidence shows that simply replacing building lighting and HVAC equipment with more energy-efficient technology is only partly a solution. How a building is used, operated, adapted, and integrated have much larger impacts than equipment and systems—and have often marred well-meant retrofit efforts.

A new chapter in building energy efficiency is beginning, driven by public awareness, building benchmarking transparency, rapid improvements in controls and real-time reporting technology, and increasing stakeholder expectations on sustainable performance. Continuous performance management that integrates controls, management, operations, and tenant engagement is emerging as an effective and inexpensive response.

Always Be Improving

An ongoing process of continuous energy performance improvement is an important part of an energy management strategy, which must also involve and engage building operators, managers, and tenants. Once optimized, an ongoing or continuous commissioning process needs to be introduced to maintain performance, which must include:

• Ongoing performance measurement, in place to track performance of key performance indicators like tenant HVAC complaints, energy performance, and indoor air quality, which are monitored and acted upon;

• Disciplined building operations, where adjustments to operating parameters, schedules, and repairs are well documented and opportunities to correct the root cause of problems are identified and taken;

• Change management process, in place to regularly review the data collected through ongoing performance measurement and disciplined building operations so the root cause of issues are investigated, identified, and corrected;

• Supply chain and team alignment and coaching, in place to ensure the goals of a team are aligned with the desired key performance measurements goals that have been set; and

• Ongoing continuous improvement to update targets and processes to continue to move the bar higher against industry benchmarks and the increasing capabilities of a building team.

Edwin Lim, P.Eng., is president and Ian Theaker, P.Eng., is senior associate of Ecolibrium Strategies.