The recent failure of a critical water transmission line in Calgary, which severely impacted the supply in city’s reservoirs and its ability to move water across the city, highlighted the dire state of municipal infrastructure in Canada and has renewed calls for governments to provide sustained funding to fix the issue.

The impacts of these failures go beyond water rationing, extending far into the construction industry, slowing many important infrastructure projects to a crawl, and some to an abrupt halt.

During a recent webinar hosted by ReNew Canada and its sister publication Water Canada, a panel of experts discussed the lessons learned from Calgary’s experience and how the industry can be an integral part of the solution moving forward.

What were the most significant challenges faced during the failure and repair of Calgary’s water main transmission line?

Frano Cavar (Director, Public Affairs and External Relations, Calgary Construction Association): When the pipe broke in Calgary, there was significant economic impact on the construction industry. For example, after the initial state of restrictions, there was a hot works ban and a fire ban. An industry that was adjacent to the issue was suddenly affected and people didn’t realize the impact that would have when restrictions were put in. One piece of infrastructure broke down, but it affected so many different subsections, in particular the construction industry.

Frano Cavar (Director, Public Affairs and External Relations, Calgary Construction Association): When the pipe broke in Calgary, there was significant economic impact on the construction industry. For example, after the initial state of restrictions, there was a hot works ban and a fire ban. An industry that was adjacent to the issue was suddenly affected and people didn’t realize the impact that would have when restrictions were put in. One piece of infrastructure broke down, but it affected so many different subsections, in particular the construction industry.

Owen James (National Leader, Strategic Advisory Services, Associated Engineering): The level of awareness around our water systems is somewhat limited. It’s inevitable that there could be issues or failures and sometimes we’re not prepared for that. The efforts to reduce water consumption as they enact the subsequent repairs is probably a little bit more challenging from a communications perspective. How do you communicate to a council when your system is still running fine and dandy? We need to invest in our infrastructure even though everything looks like it’s going fine. One of the biggest challenges is how we communicate this stuff.

Owen James (National Leader, Strategic Advisory Services, Associated Engineering): The level of awareness around our water systems is somewhat limited. It’s inevitable that there could be issues or failures and sometimes we’re not prepared for that. The efforts to reduce water consumption as they enact the subsequent repairs is probably a little bit more challenging from a communications perspective. How do you communicate to a council when your system is still running fine and dandy? We need to invest in our infrastructure even though everything looks like it’s going fine. One of the biggest challenges is how we communicate this stuff.

John Gamble (President & CEO, ACEC—Canada): People only seem to talk about infrastructure when something like this happens. It is so essential in every aspect of our lives; it’s not just the lack of water coming out of your pipe in the morning, it’s the disruption of business. And if you look at the rest of our linear infrastructure, it’s how commerce happens, how people get to their jobs; it also connects communities. Infrastructure touches us every single day of our lives socially, economically and environmentally, and we need to give it the seriousness it deserves.

John Gamble (President & CEO, ACEC—Canada): People only seem to talk about infrastructure when something like this happens. It is so essential in every aspect of our lives; it’s not just the lack of water coming out of your pipe in the morning, it’s the disruption of business. And if you look at the rest of our linear infrastructure, it’s how commerce happens, how people get to their jobs; it also connects communities. Infrastructure touches us every single day of our lives socially, economically and environmentally, and we need to give it the seriousness it deserves.

Stephanie Bellotto (Manager of Government Relations, Ontario Sewer and Watermain Construction Association): From an Ontario perspective, the two storms we experienced this summer were considered once in a hundred-year storms, but now they’re happening a lot more frequently. The flooding, as a result, put the state of Ontario’s infrastructure into the spotlight, which is otherwise treated as out of sight out of mind. We’re still using the infrastructure built by our grandparents; the capacity built from 50 years ago is not able to support the growing population that we’re seeing today. Governments are now aware of this and [are] making substantial investments in our water, wastewater and stormwater infrastructure; but we’re also busy playing catch up with having to repair our aging infrastructure while also expanding to accommodate for this growth. There needs to be a long-term solution to fix how we can properly fund and expand this critical infrastructure.

With an urgent need for sustained government funding to address aging infrastructure, what strategies can secure long-term investment in municipal infrastructure?

John Gamble: First, we need to understand the current state of our infrastructure. We need to have an adult discussion of what kind of infrastructure we need in this country to be economically viable and environmentally viable to improve our social and cultural spaces, and what that should look like in 10, 20, and 40 years. Then we can make data-based, evidence-based policy decisions. It’s not just about mitigating risk. Our infrastructure needs to be viewed as an investment to be leveraged, not an expense to be minimized.

Owen James: I totally agree that this is the crux of asset management, having that data and evidence to support decision making. One of the challenges is the asset manager, the person collecting that data, is not the person making the decision and releasing the funds and initiating projects. We need to somehow communicate what the implications of this data and evidence are to the decision makers. One of the critical things is being able to adequately articulate risk. We need to articulate the results of that data in terms of what it means for people, the environment, and society. What are the economic losses? Somehow we’ve got to be a little better at articulating the implications of the risks that as society we’re facing from our water infrastructure.

Frano Cavar: When municipalities are creatures of the province, their powers come directly from the province. When it comes to municipal infrastructure, they can’t do it alone because their taxation in the way they raise revenue is so limited. As a result, I think we need to have that broader conversation of what is the provincial role in managing municipal infrastructures. How do you communicate to Canadians the state of our infrastructure and these are why we need to make these investments?

Stephanie Bellotto: The storms experienced in Ontario put the state of our underground infrastructure into the spotlight; or else it’s usually out of sight out of mind. The full cost recovery model would be a great solution until [the] municipalities’ long-term plans of funding this infrastructure. There needs to be long-term solutions. The majority of municipalities in Ontario use age-based assessments, meaning that if a pipe is deemed to have a lifespan of 80 years, they’re not going to look at it until the next 80 years. We recommend to a lot of municipalities that they should be conducting regular conditions-based assessments.

Owen James: When we make decisions today about our infrastructure, we’re often thinking about capital. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about the benefits. When we’re having that conversation about cost, it’s not just about the cost today, it’s the cost tomorrow and the cost in 50 years. When municipalities are looking at their business cases, are they taking that into consideration? There’s a responsibility for everyone all around to have that long-term thinking costs, benefits, risks, all of those different dimensions.

How can new technology and construction techniques improve the quality of water infrastructure and increase its lifespan?

Stephanie Bellotto: It helps to capture the condition of the pipe based on flow rates; so by doing this, municipalities can rehabilitate our systems when necessary and avoid system failures that disrupt life’s necessities.

Owen James: If you think about when that pipe went in 50 years ago, all of this technology that we take for granted today didn’t exist. We have the computing power to take all of this data and store it and do something about it. We are storing them using SCADA systems and telemetry systems, and with that electronic data, we’re now able to apply some sort of analytics and intelligence. I think a lot of technologies are grappling with the challenge of advanced metering infrastructure. There is a huge opportunity here with condition, equipment, thermal and electrical monitoring, etc. A conversation like this wouldn’t be right without mentioning AI. We’re going to see AI being able to make sense of all this data and being able to provide the opportunity for essentially real time monitoring.

John Gamble: To do that, we need to rethink procurement fundamentally. Public procurement is based on how much it costs now. It doesn’t do a very good job of bringing in life cycle; it actually discourages innovation; because even if you’re only looking at 20 per cent price, you’re going to minimally interpret the scope to be competitive. So that’s the first strike against innovation. Then you transfer the risk onto the proponents, so you don’t try anything new because it doesn’t make business sense to take on all the risk yourselves. And thirdly, a lot of public owners… want to own the intellectual property and in many cases they aren’t even sure why. So sometimes public procurement is a big exercise in whatever you do, do not innovate. And we need to reward innovation. We need procurement that takes a life cycle view, not how much is it costing now but how much is this going to cost over the project lifespan?

Charlie Evans is the Associate Editor of Water Canada.

[This article appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of ReNew Canada.]

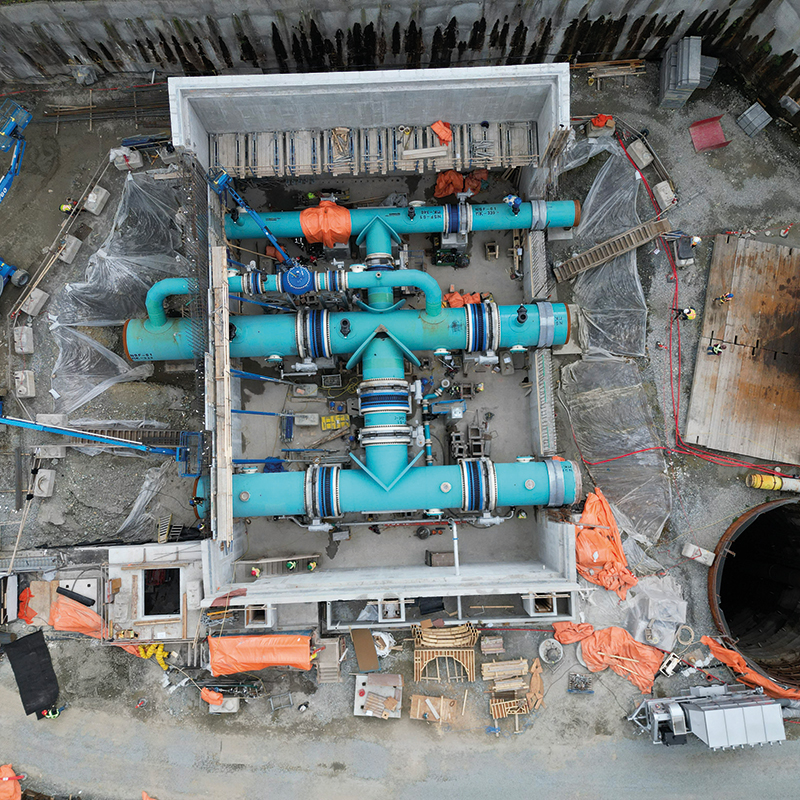

Feature image: The impacts of water infrastructure failures go beyond water rationing, extending far into the construction industry, slowing sometimes halting important projects. (Metro Vancouver)