By Mark Douglas Wessel

It was ranked the No. 1 story of 2019. And while it took place in Ottawa, it wasn’t exactly the kind of story the city would like to see repeated any time soon.

The story in question was “Another Record Setting Ottawa River Flood,” which according to Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCE) was the top weather occurrence of 2019. A flood the government department declared “was bigger than the 2017 event that was then considered the flood of the century.”

The ECCE’s 2019 weather round up states that everything about the Ottawa River flood “including its size and duration was unprecedented.” An unfortunate nexus of: snowfall accumulation that was 50 per cent higher than normal for that winter; multiple rounds of heavy spring rains; and warm air from the southwest. All of which conspired to raise the Ottawa River 30 centimetres above the 2017 flood’s peak levels.

In terms of the damage done, over 6,000 homes in Ottawa and Gatineau, were flooded or at risk, roads and streets in the affected areas were closed for extended periods, ferry services were cancelled and several bridges, including the Chaudière between Ottawa and Gatineau were closed.

The sheer scale of this calamity compelled Ottawa’s city council to declare a climate emergency, including the decision to allocate $250,000 toward “accelerating climate action.” Which in turn led to the creation of a 35-page Climate Change Master Plan, unveiled in January 2020.

Revisiting the fact the city experienced two major flood events within the span of a couple of years, Julia Robinson, the city’s Program Manager for Climate Adaptation describes 2019 as “a trigger year for focussing on adaptation… the preparedness side as well as our mitigation efforts.”

In addition to the Climate Change Master Plan, which was a city-wide risk assessment, “we also did ones on our critical drinking water and wastewater facilities,” Robinson says. Work designed to “understand our risks overall (and then) narrow it down to infrastructure driven risk assessments as well.”

As a result of those efforts, the city now has an overall climate resiliency strategy called Climate Ready Ottawa, which Robinson says is “a multi year, multi phase program in part because we’re doing it slowly and… we need to do it as a collaborative approach… bringing all of our departments on board and helping them to prioritize and understand where their next steps are.”

Including of course, the city’s Water Resource Planning and Engineering Department, which plays a critical role in the city’s flood mitigation efforts; including producing its own urban flood information report.

A report comprised of a handful of key focus areas according to Hiran Sandanayake, who not only is manager of the above-mentioned department but also the chair of the National Committee on Climate Change for the Canadian Water and Wastewater Association.

“What we do holistically to deal with flooding,” observes Sandanayake, begins with planning and strategy which pertains to such essential considerations as “choosing the right thing to go in the ground or on the road or on your roof. Then there’s community design, there’s operations and maintenance, there’s risk assessment and mitigation planning.”

Recognizing it’s only a matter of when rather than if Ottawa will have to deal with future flooding concerns, Sandanayake observes that the city is taking a multi-faceted approach to adaptation that intersects with city-wide emergency management, public works and sewer management efforts. But also at the local level, residential programs.

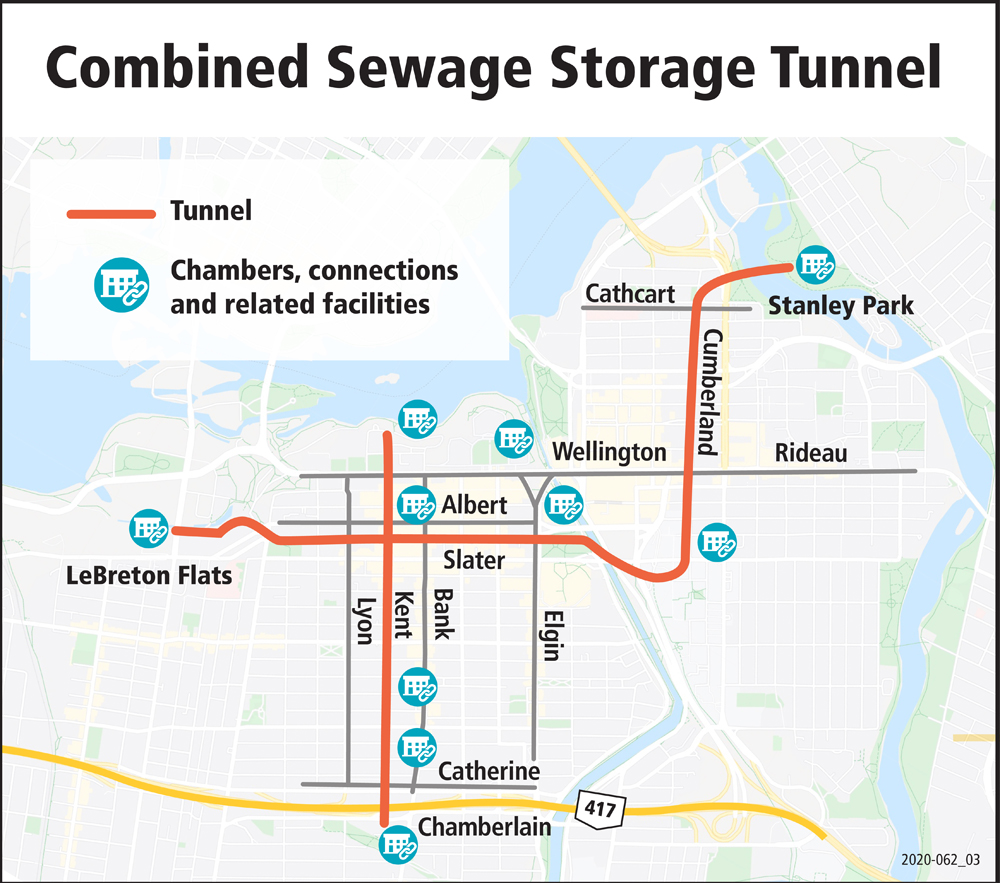

Ottawa’s $232-million Combined Sewage Storage Tunnel (CSST) was designed specifically to prevent the oldest parts of the city’s sewer system from overflowing into the Ottawa River during heavy downpours. (City of Ottawa)

Tunnel vision that’s paying off

To its credit, the city has been prioritizing separate sewer and stormwater systems dating back to 1961 when it was mandated that all new developments have separate sewers. And since then, there have been ongoing efforts to progressively separate sewers from older neighbourhoods.

Most noteworthy of those efforts has been the $232-million Combined Sewage Storage Tunnel (CSST), designed specifically to prevent the oldest parts of the city’s sewer system from overflowing into the Ottawa River during heavy downpours.

Capable of handling up to 43,000 m3 of water per event (approximately 18 Olympic-sized swimming pools), planning for the CSST’s 4.2-kilometre network of tunnels commenced back in 2009.

That was followed by an environmental assessment by Stantec, commencement of construction in 2016 a year before that first “century storm” hit the city, with the project finally opening in 2020. Stantec Consulting Ltd. and Jacobs Engineering Group (formerly CH2M Hill) completed the detailed design, contract administration and construction support services for the project, with geotechnical support from Golder Associates Ltd. Construction was led by Dragados Tomlinson Joint Venture.

Since that time, Sandanayake observes that “our performance data clearly shows that the combined sewerage storage tunnel is working. Events that would have caused overflows no longer cause overflows.”

In addition to reducing the likelihood of overflows, the tunnel temporarily stores the water so it can be sent back and treated at the wastewater treatment plant. And after the wastewater treatment plant it’s cleanly discharged back into the river. “So the high level story is pollution prevention,” says Sandanayake.

He adds that consistent with the city’s goal of maximizing the impact of such a major investment, the CSST can be used to essentially backstop future maintenance efforts.

“If the large collector sewer that crosses downtown were ever needed to be maintained in a very disruptive way, you could divert water into the tunnel and send it directly to the plant by gravity without pumping,” he says. “It also reduces flooding in some of the combined sewer storage areas… because some of the surface flooding can now be directed to the combined sewage storage tunnel.”

In many respects, the massive size of the tunnel says Sandanayake, was dictated by the fact that “we contemplated climate change (and) we contemplated future development, growth and intensification.”

Notwithstanding the success of the CSST, to put matters into perspective he is quick to add that “one of the most effective things we’ve been doing since the 60s and we’re still doing, and we’re ahead of schedule, is separating sewers.”

As a result, says Sandanayake “a lot of these small, combined sewer outfalls no longer discharge any water. Why? Because we separated all the sewers. Now there’s two sewers in the street. There’s a sanitary sewer and a storm sewer.” And every time a sewer comes up for renewal it’s automatic that it will be separated. “We’ve already pre-planned how to separate them,” he adds.

PurePave’s surface for a new condo project—the site of former flour plant—in Carleton Place eliminates the need for a stormwater pond. (PurePave)

Getting rain ready

Yet another highly successful initiative, as part of a suite of solutions to address flooding at the neighbourhood level, has been the Rain Ready Ottawa program. The program was launched in 2021 as a pilot project to encourage homeowners and businesses to do their part to keep precipitation onsite (in contrast to the past priority of shunting water away), with rebates of up to $5,000 per household tied to such actions as the creation of rain gardens, downspout redirection and the installation of permeable pavement.

To date, the program has supported more than 435 projects across 220 applications (with some homeowners tackling more than one project) and according to Robinson, is on track for 2025 to be its most successful year.

“The program demonstrates the power of seed funding to catalyze action and investment,” observes Robinson. City rebates of $600,000 have leveraged $3 million in investment by private property owners in onsite stormwater management.

More than 50 per cent of rebate applications include a permeable pavement component and one of the most successful companies involved in the installation of residential driveways has been Ottawa’s own PurePave Technologies , which to date has done over 100 driveway installs.

With up front research partially funded by the National Research Council, unlike conventional permeable paving, PurePave is made from a proprietary mix of resins, plant-based polyols (contributing to the surface’s flexibility, toughness, weather resistance and longevity), metal powders, recycled materials and granite aggregates. Combined with a 30-centimetre permeable base, the company’s site claims the surface is capable of handling 38,000 litres of water per hour per square meter.

According to PurePave CEO Taylor Davis, in the past, permeable paving wasn’t all that effective when it comes to rainwater retention or structural performance. “Previously, permeable systems like brick pavers weren’t giving the industry a very good name because with only six per cent of the total surface area infiltrating water, that six per cent clogged quickly,” “So, you’d still have most of the runoff going to the street. The original traditional systems like porous concrete and asphalt had also failed in winter conditions. But when you put PurePave down, none of that water is going to be reaching the street and its durability is suitable for parking lots or roads. So that’s what really changes the game.”

Since its founding in 2012, PurePave’s primary focus was paving residential driveways in Canada and the U.S., but now the company is tackling larger projects at the municipal level ranging from sidewalks to parking lots to surfacing for Green Streets projects in cities such as Toronto and Ottawa.

The road ahead

Yet another application for permeable pavement for municipalities buying into the strategy of creating a sponge city, is to use this surface along roadways to better manage stormwater and reduce runoff.

Just last year, New York announced plans to install permeable pavement along a seven mile stretch of flood prone roads that will cost USD$32.6 million and by the city’s estimate it will prevent millions of gallons of stormwater from overwhelming the sewer system annually.

According to Davis, the cost of paving a similar stretch of road in Canada using PurePave “would be a fraction of that cost,” adding that “wherever storm systems are at-capacity, having issues but not yet at the end of their lifecycle, PurePave road shoulders can be used to save > $4 million per kilometer. Fixing the stormwater issue in the short term, buying time until the renewal dates arrive.”

Toward that end, PurePave is currently working with the City of Toronto on a pilot project, and is also in discussions to consider doing a similar pilot for the City of Ottawa, an initiative Sandanayake confirms is currently being considered. “Staff continue discussions regarding several factors including scope, cost, and complexity, to determine the feasibility of integrating this into a design project.”

Tie to that potential pilot as well as other future flood mitigation initiatives, he stresses that the city’s overarching goal moving forward “is to consider new ways of doing things that have more benefits. Even if it has an additional cost over its life cycle or more operations or more maintenance, we rationalize that may be worth it because we’re getting not only one benefit, but maybe two, three benefits that we can quantify.”

From a big picture point of view, Robinson observes that “all professionals, all people that support municipal growth and renewal and operations need to start applying that climate lens and thinking about how their piece of the puzzle has to be thinking about how we are preparing for those future conditions, because those future conditions are coming for sure.”

Reaffirming Sandanayake’s point about prioritizing investments that deliver multiple benefits, Robinson offers that “we need to think about initiatives that deal with flooding but also help against heat. So, think from multiple perspectives. Design for the future. And start breaking down the barriers between the construction, the renewal folks and the operational folks. Because sometimes there may be an operational maintenance response that can help extend the life of your infrastructure assets and the need for renewal.”

Mark Douglas Wessel is an urban journalist and communications consultant. He writes a regular column called “Green Living” for Postmedia.

[This article appeared in the November/December 2025 issue of ReNew Canada.]

Featured image: Capable of handling up to 43,000 m3 of water per event (approximately 18 Olympic-sized swimming pools), planning for Ottawa’s CSST’s 4.2-kilometre network of tunnels commenced back in 2009. (City of Ottawa)