By Steven Peck and Shayna Stott

A trip up to the observation deck of the CN tower would find tourists and locals marveling at the growing skyline, picking out parks, islands and ravines and perhaps commenting on the endless traffic on the Gardiner Expressway. Dozens of new buildings have been added to this view over the past 15 years, and it doesn’t take much time for the even the untrained eye to spot the many green roofs high above and largely invisible to the downtown crowds.

While largely invisible, these roofs provide a suite of benefits to the building owners and the city. Light weight, extensive green roofs retain approximately 60 percent of the rain that falls on them, and can help to reduce flooding impacts during severe storms, while taking some of the strain off our aging stormwater infrastructure. Blue-green roofs which combine detention underneath a green roof, with retention in the layers of a green roof, are able to manage even greater quantities of rainwater and provide opportunities for its controlled release. Green roofs reduce energy bills, and even extend the life expectancy of the water proof membranes beneath them.

Green roofs are part of a growing worldwide trend towards investing in the development of ‘sponge’ cities through the use of green infrastructure. These are cities where impervious roofs, road ways and parking lots are redeveloped to capture, slow down, infiltrate, evaporate and transpire stormwater rather than shed and transfer it to overloaded sewer systems. With sponge cities, stormwater is perceived as a resource, to be used to help sustain plants which provide us with numerous benefits. In addition to green roofs, sponge city development often includes investments in green streets, bioswales, urban forestry, temporary flooding of parks, ponds and greenways, and porous paving in a treatment train approach. The treatment train begins with managing stormwater at the roof, down the sides of a building, around the building as it moves downward towards receiving water bodies, such as rivers and lakes or treatment plants. The city of Copenhagen has been tremendously successful at limiting flood damage from intense cloud burst rain events in several districts through this approach.

“Implementing sponge cities is key to securing urban resilience and ecological health. By allowing cities to naturally absorb and repurpose rainwater, we not only combat flooding but also transform our urban environments into lush, green havens that thrive in harmony with nature’s cycles, countering the inefficiencies of traditional un-resilient gray infrastructure”, says Professor Kongjian Yu, an internationally renowned landscape architect who coined the term ‘sponge cities’ and has been implementing this approach in dozens of Chinese cities since the late 1980s.

Toronto has been moving in both directions grey and green at the same time, with multi-billion dollar investments in grey infrastructure on the waterfront to address combined sewer overflows and flooding, and a suite of green infrastructure programs and policies. For example, a google satellite view of Toronto provides the best way to see the changing roofscape. Green roofs identify a generation of buildings constructed under the City of Toronto’s Green Roof Bylaw. Next year marks the 15th anniversary of the City’s bylaw, the first in North America to require green roofs city-wide and to establish the standards that govern their construction. This year is also the 20th Anniversary of the first international green roof conference in Toronto – CitiesAlive.

Since 2010, the Green Roof bylaw has driven the green roof industry to deliver over 1000 green roofs, covering over 1,000,000 sq m (10,700,000 sq ft); an area equal to more than 185 NFL football fields. Green roofs are a basic building feature in Toronto; contributing to meeting the Toronto Green Standard (green building requirements); stormwater management and vibrant outdoor amenity spaces at the same time.

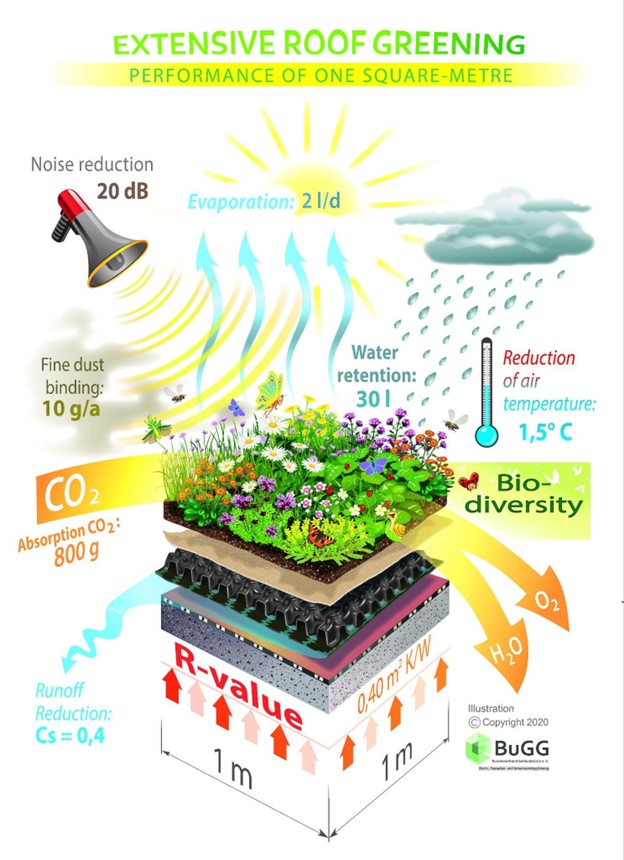

These lightweight green roofs confer a wide range of benefits, in addition to helping manage stormwater. The figure below is a summary of the average benefits generated by one square meter of extensive green roof, developed by BuGG, the German Green Roof Industry Association. The benefits are based on average values and the diagram does not include the human health and well being benefits that can be generated from accessible green roofs. Air temperature reductions are key to helping mitigate the increasing frequency of heat waves by reducing the urban heat island effect.

Toronto’s multipronged Green Roof Strategy emerged from years of successful advocacy by Green Roofs for Healthy Cities long before the City had the ability to require green roofs. The first Green Roof Strategy adopted in 2006, focused on building awareness and industry capacity in those early years, identifying the need for incentives and city leadership – two key pillars of the City’s green roof program today.

Toronto’s approach brings together regulation with incentives to support voluntary green roofs through the Eco-roof incentive program; and municipal leadership through a city policy requiring all city-owned facilities go above and beyond the minimum requirements of the bylaw. This approach has been successful with city projects delivering a range of green roofs that are amongst the largest in the city and include biodiverse green roofs. The Eco-Roof Incentive Program draws sustainable funding from the cash-in-lieu provisions of the bylaw and has funded 535 cool roof and 115 green roof projects.

Toronto successes have relied not only on the green roof industry’s response but also leadership within the development industry. Green building leaders gained experience with green roofs in the early years, enabling meaningful feedback on making a requirement work for new development.

The search for solutions to the City’s environmental challenges resulted – intentionally or not – in a thriving local industry that has impacts outside of its borders – an outcome only possible through the willingness of green roof suppliers, installers, landscape architects, engineers and developers to all be at the table to deliver solutions.

With growing infrastructure needs and increasing costs, cities need to use all of the tools in their toolbox – green and grey – in order to adapt to the challenges of climate change. This typically means moving aggressively towards spongier cities, which will deliver greater value for money and better places to live.

Toronto’s leadership on the green roof front demonstrates that we can make our infrastructure dollars go farther through well crafted policies and program. Join us as we celebrate 20 years of green roof and green infrastructure progress and explore major future developments like the Downsview Community, and the Don River flood control and re-naturalization project at CitiesAlive in Toronto November 6 to 9, 2024. Learn from experts such as engineers, architects, landscape architects, researchers, developers and contractors from across North America who have embraced the concept of sponge cities and are working to implement them. Join us at www.citiesalive.org for more information and to register.

Steven Peck, GRP, Founder and President, Green Roofs for Healthy Cities and Shayna Stott, Senior Planner, City of Toronto.

Featured image: The new Canary District, in east Toronto is home to multiple green roofs and integrated sponge city stormwater management. At scale, green roofs can help reduce the impact of extreme weather and the urban heat island. (LiveRoof Ontario Inc.)