Across Canada, a handful of energy utilities have been thinking outside the box. Rather than providing individual energy services—such as electricity, natural gas, and heating and cooling—strictly under the auspices of affordability and reliability, they are pioneering a new age of energy delivery that advances a more integrated and holistic view of energy at the community level.

Consider ENMAX Corp., which has provided electricity in Alberta for more than 100 years; since 2011, one of the fastest growing parts of its business is delivering heating through a district energy system to downtown Calgary. Or take FortisBC, which is proactively procuring renewable natural gas from landfills throughout British Columbia, integrating it into the company’s supply network, and delivering it to natural gas customers. And look at PowerStream, using advanced systems technology from General Electric to pilot a microgrid at its headquarters in Vaughan, Ontario, test driving the ability of renewable electricity technologies to fully meet local demand.

Welcome to the age of smart energy communities, where priorities and opportunities around efficiency, reliability, costs, and greenhouse-gas emissions converge. So what does a smart energy utility look like—and how will it prosper in this brave new world of smart energy communities?

Smart energy communities are defined by three key features, and the utility needs to support and enable each of them. (To see how this dynamic works, visit questcanada.org/thesolution.)

1. Integrating Conventional Energy Networks

Integrating conventional energy networks means a community’s electricity, natural gas, district energy, and transportation fuel networks are better coordinated to match energy needs with the most efficient energy source. This is enabled by “smart energy networks” and the advanced technology systems that are giving utilities increased capacity to manage the flow of energy in their networks.

The role for the smart energy utility here is to collaborate with other utilities in smart energy networks to identify when and where its energy is the most efficient choice for consumers. When electricity is the most efficient energy option—such as for appliances, street lighting, or vehicle charging—then the electricity network can be tapped. And when natural gas is the most efficient option—such as for heating buildings and domestic hot water or again for vehicle fuelling—then it is on hand. The same evaluation is made for other conventional energy networks at the community level.

Meanwhile, where it can supply supplementary energy services that improve the efficiency of the network, the Smart Energy Utility needs to consider market growth. Electric charging for vehicles and liquefied natural gas for heating in remote communities are just two examples of supplementary services that are offered by energy utilities in some communities and that can significantly improve efficiency.

Smart energy networks are also about empowering customers to make better energy decisions themselves. Smart meters, time-of-use programs, and energy conservation programs can be valuable toward these ends, by both informing customers and incenting them to use energy wisely. The Smart Energy Utility also enlists a range of other engagement tools, including social media, public demonstrations, and consultations, as well as more sophisticated engagement programs like Enbridge Gas Distribution’s Saving By Design program, where the gas utility works directly with developers and builders to optimize the energy performance of new buildings.

2. Supporting Smart Land Use Decisions

The second feature of a smart energy community is that it makes smart land use decisions, recognizing poor land use planning can equal energy waste.

Utilities can support smart land use decisions in two ways. The first is to participate with local governments and other community stakeholders in community energy planning initiatives. Community energy planning is a process in which stakeholders map energy demand and supply, shape growth, and integrate operational planning to improve energy efficiency on a community- or regional-wide scale.

Union Gas is a natural gas distribution utility that is proactively participating in community energy plans across its Ontario territory. In so doing, it is able to point out where its energy services are the most efficient option for communities, as well as to ensure that its operational planning and the municipality’s growth planning are aligned.

The second way that utilities can support smart land use decisions is by incenting intensification through infill and brownfield development. Horizon Utilities, the electric distribution utility in Hamilton and St. Catharines, Ontario, for instance, has introduced an Infill Development Program that removes system charges from connection costs for customers who develop and build along existing utility lines. The result is a more efficient and profitable use of Horizon’s energy infrastructure, not to mention other community infrastructure investments, as well as denser communities that result in less energy being wasted in traffic and less energy used to deliver key services such as water, policing, and emergency management services among others.

3. Harnesses Local Energy Opportunities

The third and final feature of a smart energy community is that it harnesses local energy opportunities.

Here the smart energy utility does three things: integrates local energy opportunities that complement its existing system, accommodates two-way flow, and prepares for modest adoption of behind-the-meter energy production.

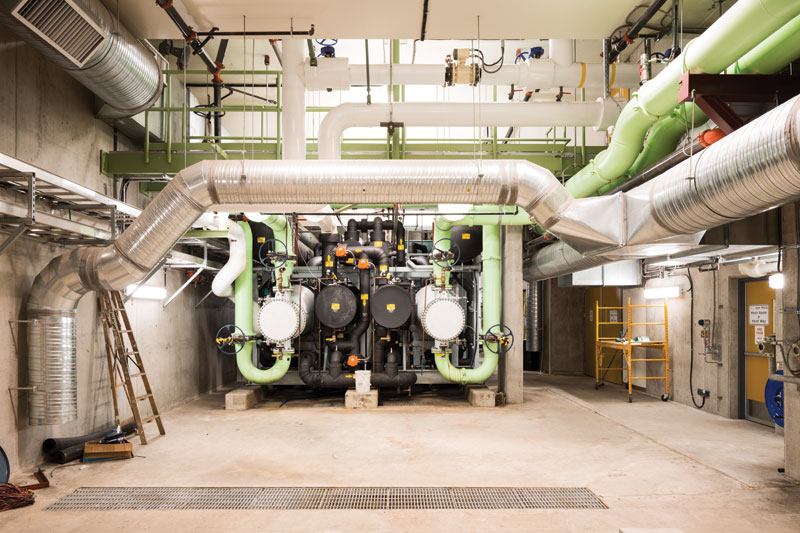

Integrating local energy opportunities begins with recognizing that there are untapped energy opportunities throughout the community. Electric utilities can look for renewable and distributed electricity opportunities; natural gas utilities for renewable natural gas opportunities; and, district energy utilities for heat capture opportunities like the City of Vancouver does with sewage heat at its Southeast False Creek Neighbourhood Energy Utility.

An underutilized opportunity for integrating local energy opportunities is combined heat and power (CHP), which requires physical integration of electric and natural gas energy systems. In Ontario, both electric utilities (such as Oshawa Power and Utilities Corp.) and natural gas utilities (such as Enbridge Gas Distribution) have been proactive in identifying opportunities to integrate CHP. Meanwhile, Markham District Energy (MDE) is successfully recovering heat from four natural-gas CHP systems, in turn providing up to 60 per cent of MDE’s winter heating peak while feeding 15.5 MW of electricity into the local grid.

The second way that the smart energy utility needs to support harnessing local energy opportunities is by accommodating two-way flow—in other words, energy produced by utility customers and fed into existing energy networks. The Province of Ontario’s microFIT program, for instance, has led to a surge in typical energy consumers also becoming pro-sumers by establishing the program and regulatory bases for accommodating customer-produced renewable electricity onto local grids. A range of policy, program, and regulatory approaches can achieve the same outcome in other jurisdictions.

The third and last way the smart energy utility needs to support harnessing local energy opportunities is by preparing for modest adoption of behind-the-meter production. While the utility will undoubtedly continue to be the chief provider of energy services, there are some cases where behind-the-meter or off-grid energy production is in the broader interest and can help support smart energy communities.

Utilities will continue to be the chief providers of these energy services in a smart energy community. However, the smart energy utility is the utility that is proactively collaborating with other community-level stakeholders, and is aggressively adopting new technological and program innovations in order to integrate conventional energy networks, make smart land use decisions, and harness local energy opportunities.

Eric Campbell and Richard Laszlo work at QUEST.