Managing utilities poses one of the largest risks in urban construction.

By Richard Harris

Beneath the ground or towering overhead, every urban centre has hidden networks of cables and pipes that keep us connected. If a construction project jeopardizes this delicate utility network, the community risks losing the power, telecom, water, gas and drainage services that are so integral to our daily lives and businesses.

Before you ever break ground on a project, you need to know exactly what exists underground and overhead, and how you’ll manage that infrastructure. This enabling works strategy involves many stakeholders and requires a high level of partnership and accuracy to succeed.

Despite various planning and utility relocation guidelines, the challenges surrounding utilities coordination exist across construction projects in every Canadian city. By exploring examples of real-world risks and approaches to utilities management, we can identify the tactics that are working well and build a concrete set of best practices to better manage this complex issue.

What is utilities coordination?

The Transportation Association of Canada defines utilities coordination, or utilities management, as “the coordination of projects between public land authorities and utility service providers. [It’s a] process [that intends] to provide early identification and resolution of possible delays and confusion that may add unnecessary complexity and cost to a project.”

Consisting of key planning, design and construction phases, utilities coordination is a project in and of itself. Ideally complete in the years leading up to the main construction project, utilities coordination enables the project team to begin construction with clear pathways.

Why is utilities coordination challenging to manage?

Major projects rely on multiple utility agencies and stakeholders coming together to work on a project that is not of their creation. Depending on right-of-way, relocating utilities can come at the expense of a utility agency, and its preferred solution may not align with the upcoming project’s objectives and priorities.

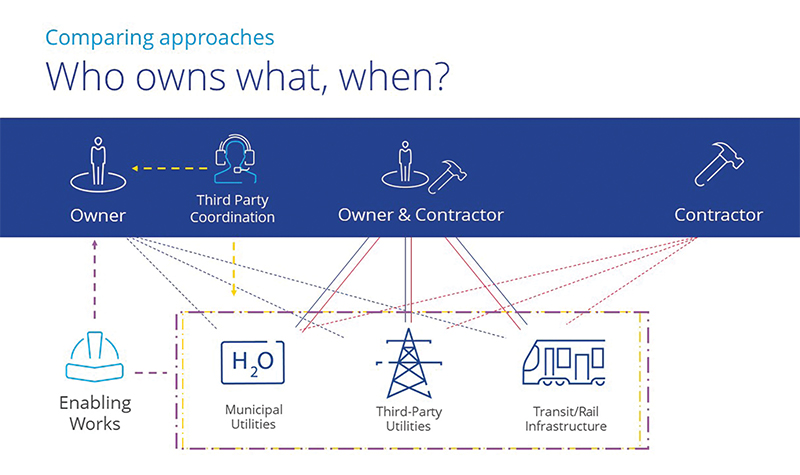

To complicate things further, there’s a lack of consistency in how public land and utility agencies operate. The responsibility for utilities management also varies depending on a project’s construction approach—often leading to an important question, “How can we best manage utility risks?”

Take, for example, news we’ve seen about gas mains, watermains and other utility infrastructure that have been adversely impacted by construction, causing major service disruptions, traffic delays or worse.

A Light Rail Transit (LRT) project in eastern Canada faced these challenges. To mitigate roadway closures, a section of the project was bundled with a highway expansion project. With multiple stakeholders involved, the project teams and road authorities came together to complete the necessary enabling works. Despite best efforts and cooperation from the utility agencies, the contractor struck a gas main during construction—leaving a major highway inaccessible for several hours while the pipe was repaired.

So, how did this happen? The design and construction works were well coordinated, but the discovery that the as-built drawings on file were slightly off came too late. As-builts are vital to locating existing utilities. Many municipal and utility agencies keep them readily on file for this purpose. The accuracy of these files, however, can vary based on the agency’s administrative and quality assurance protocols.

Was this avoidable? Yes.

Inaccurate or incomplete as-builts are one of the known risks that a project may face. Although not the sole cause of coordination challenges, uncertainty, inconsistency and lack of rigour surrounding who should own and manage utilities coordination, as well as related issues resulting from insufficiently informed contracts, can lead to project delays and high project costs. As a result, contractors are becoming more reluctant to bid on major projects where they are expected to assume utility risk, as the stakes are just too high.

When utilities coordination goes wrong

This experience is a common example of what can go wrong with utility coordination, despite the best of intentions. But what happens when planning and communications break down or self-interests conflict?

When it comes to utilities, the preliminary planning and enabling works that go into a project can greatly impact the overall schedule and budget. A project’s enabling works rely on the successful engagement and cooperation of all impacted utility agencies, road authorities and/or stakeholders. In some cases, there is very little guidance on how to best engage these agencies, so it’s not only natural, but a fiduciary duty, for each entity to focus on priorities and projects that serve their respective interests.

This is the case for a major program of work in central Canada, where utilities coordination has been on the critical path and continues to have a significant impact on cost and schedule. The utility agencies involved provide vital infrastructure to support the city but are governed by complex regulations and agreements that are often outside the project owner’s direct control or influence.

In the earliest stages of design development, three project teams came together to manage utility relocations and enhancements as a key part of the program’s scope of work. Despite this early acknowledgement, the program has progressed substantially through design and has been under construction for more than two years, with outstanding issues surrounding agreements for cost sharing, coordination and integration of utility design.

Discussions with utility agencies started early, but the identified solutions extended project timelines and exceeded the owner’s budget. Protracted negotiations began with the expectation that the program owner would fund most of the costs, including some of the aging utility infrastructure replacements. Design restrictions imposed by the utility agencies, like tethering to existing structures or installing below new construction, limited technical solutions. Ultimately these complications resulted in a need to seek legal representation to reach a resolution.

Utility coordination has both complex technical and legal requirements. Understanding the impact of pre-existing utility agreements, overarching utility plans and stakeholder priorities needs to be factored into a project plan early on, along with risk mitigation strategies.

What’s been working well?

Having a firm understanding of utility risks, and assigning those risks to the parties best able to manage them is a common strategy. How you approach utilities coordination can make a big difference as well.

With so many stakeholders, agencies and regulatory authorities involved, a utilities coordinator or coordination team must maintain clear and consistent lines of communication. The two examples we’ve explored so far represent very different approaches—one placing the coordination responsibility on a single entity, and the other consisting of three separate teams coming together to coordinate the utilities on a project.

Simplifying the coordination approach and limiting responsibility to a single entity gives everyone on the project a single point of contact for communication. If the entity responsible for coordination can dedicate a team to focus solely on utilities management, all parties can benefit. Without the added pressures of managing utility risks, stakeholders, consultants and contractors can focus on their areas of expertise and the primary project goals.

Identifying a single entity to manage utilities also enables that team to consider the bigger picture. In urban centres, there are often several construction projects underway. By considering current and future projects that are likely to draw more power or place a higher strain on the existing utility infrastructure, the coordination team can approach utility agencies with a comprehensive plan that’s likely to benefit all parties.

This is the approach a western Canadian city is using for its new LRT project. The city acknowledged the cost and schedule risk associated with delivering the utility relocation work as part of its main contract. On this basis, it selected a construction management approach, engaging the expertise of the contractors in the pre-construction phase, allowing for single entity utilities coordination. Working as an extension of the city, the construction manager is able to leverage the city’s pre-existing relationships with third-party utility agencies, which is helping them achieve desirable results.

The term of many major transit projects is often so long that other impacting projects must be considered. By factoring in upcoming projects along the alignment, the team can better interpret future utility needs with each provider and mitigate the risk of continuous utility rework and ongoing disruption in the coming years.

In most major urban centres, cost sharing is governed my municipal bylaws. This may reduce the cost risk to the owner, but working collaboratively with third-party utilities can further reduce the broader cost impacts of disputes, delays and claims.

Minimizing risks

There are several steps project owners can take to reduce utility coordination risks.

- Start early: enticing all parties to share their five to 10-year capital plans is a good starting point.

- Dedicate a team: identify and dedicate a team to manage utilities coordination and invest in your relationships with third-party utility providers, regulatory agencies and impacted stakeholders. Consider creative strategies such as seconding and co-locating utility staff to effectively engage and align third parties.

- Invest in locates/as-builts: survey, map, locate and update all utility records in the right-of-way and vicinity of the project. Use technology, such as GIS and GPS, to improve accuracy and transferability.

- Have a plan: build a utilities-specific risk management plan that identifies solutions to mitigate both known and unknown risks. Update and report on the plan regularly over the life of the project.

- Define the budget: outline anticipated relocation costs based on the plan, and allocate contingency funds for both known and unknown risks. Be cognizant of existing agreements and transparent with stakeholders, third-party utilities and funding partners regarding cost responsibility. Consider a project contingency for unknown utility risks that falls in line with existent or non-existent agreements between the parties.

- Prepare for conflicts: familiarize yourself with the agreements, laws, regulations and right-of-way proceedings related to utilities coordination. Prepare a governance plan to clearly define the roles, responsibilities and contractual obligations of each stakeholder, third-party agency and authority. Identify a swift means for escalation and resolution.

- Avoid transferring risk to the contractor: allow the main contractor to manage utility relocations only if they have negligible risk, are within the owner’s right-of-way, and it is more efficient and cost effective for them to do so. If this is not the case, the responsibility of the relocate should default to the owner, thereby minimizing project risk.

Although there’s no panacea to solving this large and complex issue, utilities coordination is becoming widely recognized as a key project component, and as one of the largest risks facing major urban construction projects today.

By listening and learning from others, we can build on practices that are working well, avoid demonstrated pitfalls, and develop a measured approach to managing utility risks that serve the best interests of the project and all stakeholders.

Richard Harris leads Colliers Project Leaders’ Infrastructure team across Canada.

[This article originally appeared in the September/October edition of ReNew Canada.]

Featured image: Our water infrastructure systems are aging and in dire need of repair, with many of the pipes past their service life.