By Dr. Blair Feltmate

Over the past decade, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) released three strategic reports, each sharing a common theme—the need for municipalities to prepare for the increasing threats of Canada’s two most costly climate perils, flooding and wildfire.

The first of these ECCC reports, released in 2016—The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change—devoted a full chapter to adaptation that highlighted actions communities can take to limit flood and wildfire risk. Following its release, the report largely sat on a shelf.

Next, in 2018, ECCC released a detailed adaptation guideline, Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Results. This document, which also emphasized community resiliency, was 1.5 years in the making, drawing on input from 22 subject matter experts. Unfortunately, it too followed the fate of the Pan-Canadian framework.

The third ECCC report, National Adaptation Strategy (NAS), was released in 2023. The NAS was more prescriptive on flood and wildfire protection than its predecessors, including this target: “By 2030, 80 per cent of public and municipal organizations have factored climate change adaptation into their decision-making processes.”

For two reasons, faith in meeting this new NAS target may be justified, despite the track record to date.

First, the NAS calls for an “all-hands-on-deck” commitment to mobilize adaptation, sharing accountability across multiple stakeholders—this includes federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments, NGOs such as the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, as well as the capital markets, academe, Indigenous peoples and individual homeowners.

Second, over the past few years, new guidance (developed with support from the Standards Council of Canada, National Research Council, and Canadian Standards Association) has beome available that identifies, in easy-to-follow format, practical and cost-effective means to protect municipalities from flooding and wildfire.

The importance of preparing for extreme weather, driven by irreversible climate change, cannot be overstated. For example, from 1983-2008, insurable claims for catastrophic events in Canada hovered between $250-450 million annually. From 2009 onwards, insurable losses increased substantially to a record breaking $8.5 billion in 2024 (graph on page 27). This recent loss was due, in part, to flooding in Toronto and multiple towns in southern Ontario ($940 million), floods impacting communities throughout Quebec ($2.5 billion), and wildfire in Jasper ($900 million).

Mayors, councilors and city managers need consolidated guidance to help bend down the catastrophic loss curve—fortunately, practical solutions are in hand.

Municipal flood protection

It is important to recognize that flood “protection” does not mean “prevention”. Under extreme conditions any community can flood. However, through preparedness, the probability and magnitude of flooding can be reduced – communities are not victims of circumstance.

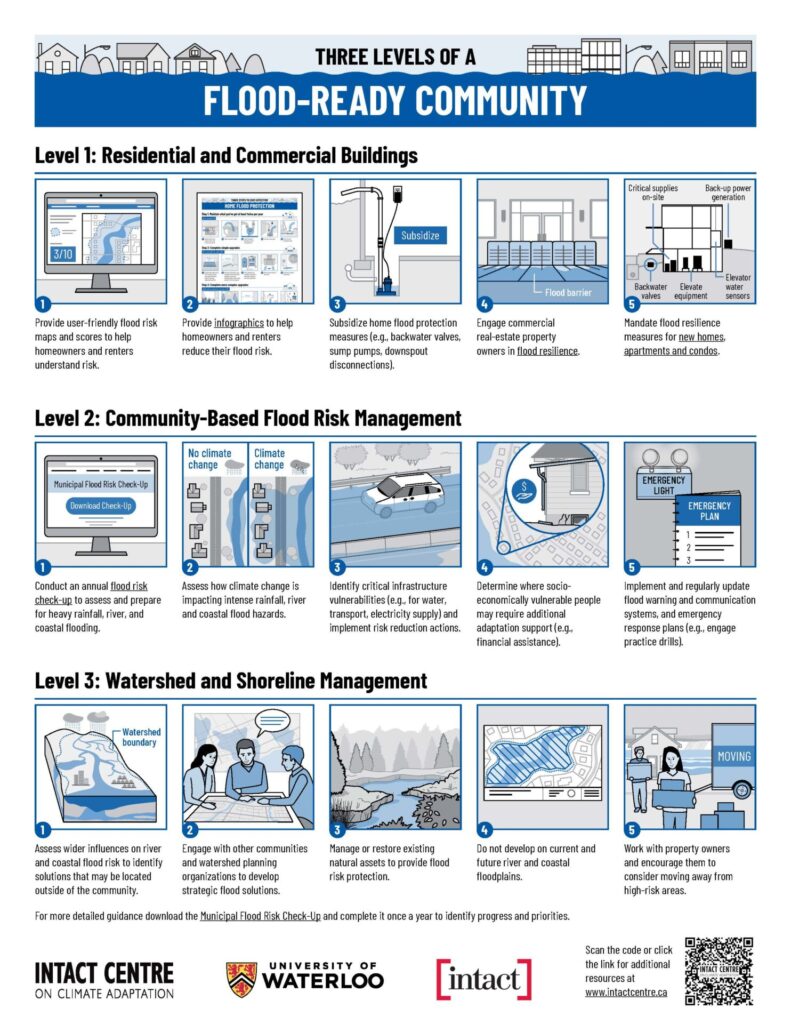

The infographic—Three Levels of a Flood Ready Community [see Figure 1]—profiles 15 actions to limit flood risk that fall into three categories: (1) Residential and Commercial Buildings, (2) Community-Based Flood Risk Management, and (3) Watershed and Shoreline Management. The actions offer a pictorial account of community flood protection described fully in A Flood Risk Check-Up for Canadian Municipalities: Tackling Flooding Together.

By way of brief description, Row 1 of the infographic profiles actions to limit flood risk at the residential and commercial property level. A core responsibility of any municipal government is to ensure that residents receive guidance on home flood protection (this guidance may be distributed in Property Tax Notice mail-outs). When presented with this guidance, within six months 70 per cent of homeowners take two or more actions to limit flood risk that they would otherwise not do. Examples of initiatives that homeowners can take can be as simple as “test your sump pump”, which involves pouring water into the sump well to determine that the pump works—and if not, fix it. Homeowners often discover sump pump failure when met with a basement full of water.

Row 2 highlights community-led flood preparedness programs, such as the municipality issuing timely flood warnings to residents.

The third row illustrates actions municipalities can take to mitigate flood risk, starting with “don’t build on a flood plain.” In high-risk areas, where flood risk mitigation options are cost-prohibitive, municipalities may subsidize homeowners to motivate them to move to a safe location.

Municipal wildfire protection

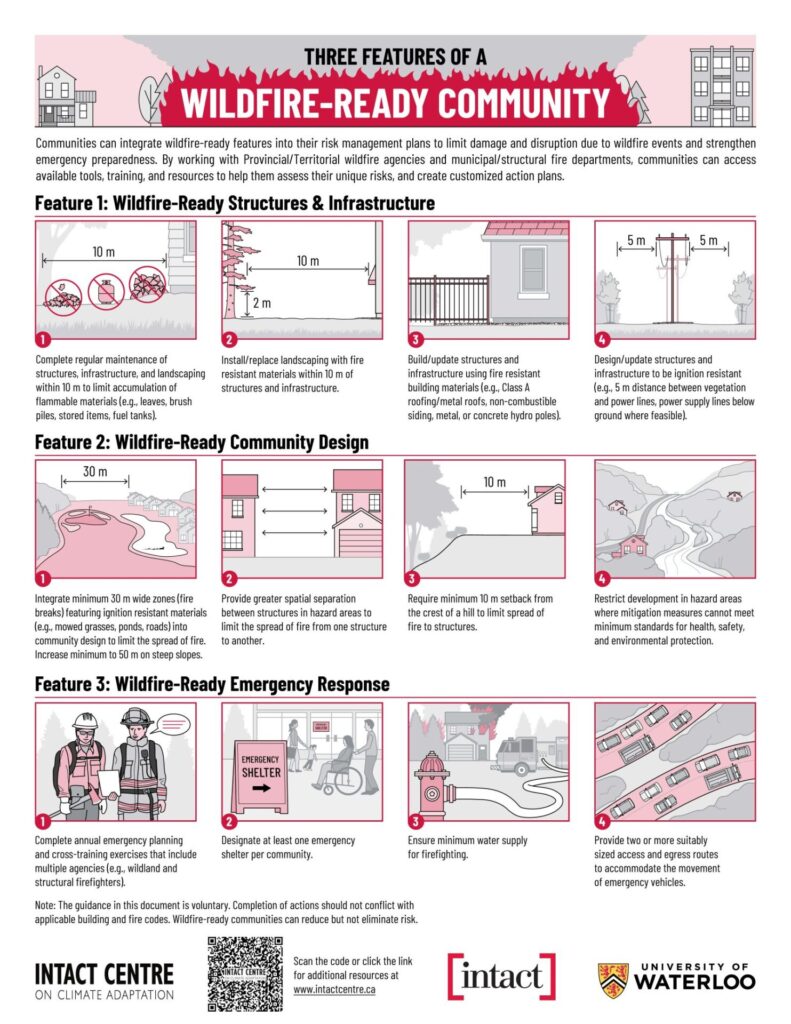

The infographic—Three Features of a Wildfire-Ready Community [see Figure 2]—profiles wildfire preparedness at three levels: (1) Wildfire-Ready Structures & Infrastructure, (2) Wildfire-Ready Community Design, and (3) Wildfire-Ready Emergency Response. The infographic summarizes wildfire protection described in Wildfire Ready: Practical Guidance to Strengthen the Resilience of Canadian Homes and Communities, and applies to communities in forested and grassland regions (sometimes referred to as the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI)).

Row 1 presents guidance that municipalities can share with homeowners to limit fire risk, including such basics as not storing firewood and propane tanks within 10 metres of the house. Homeowners should replace wooden fences, if they attach to the house, with non-combustible chain link.

When building new, as outlined in Row 2, permitting should require adequate separation of homes to limit the spread of fire from one structure to another. Municipal permitting should require a 10-metre setback of the house from the crest of a hill in the WUI, as wildfire generally travels up-slope.

The third level of preparedness focuses on ensuring communities can handle high volume resource demands during peak wildfires. For example, communities should ensure that emergency shelters have adequate space and resources to accommodate large numbers of displaced people. Communities must ensure that water pressure from hydrants remains sufficient to fight fire when entire streets or communities are under threat. Municipalities also need to prioritize that multiple egress routes are available when the capacity to contain fires is breached.

Municipalities that follow FireSmart direction can reduce their exposure to wildfire risk by up to 75 per cent.

Municipal flood and wildfire preparedness

An exponential increase in the cost of insurable claims should send a clear signal to municipalities across Canada that they must act, rapidly, to limit the growing risk of flood and wildfire.

In municipalities across Canada, 1.5 million homeowners are no longer able to obtain insurance coverage for basement flooding. In high-risk flood zones in Quebec, Desjardins Group announced that it will not renew mortgages for houses with a greater than five per cent chance of being flooded each year.

In California, in 2023, Allstate and State Farm stopped writing new residential fire insurance due to excessive risk of wildfires. California should serve as a wake-up call to implement wildfire protection in forested communities across Canada.

Canadian municipalities—most of which still address flood and wildfire risk through “reaction” rather than “pro-action”—must embrace adaptation.

ECCC, working with agencies such as the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, Insurance Bureau of Canada, Canadian Standards Association, Standards Council of Canada, and National Research Council, collectively have the pulpit to promote community flood and wildfire protection nationally. A solid commitment by these agencies could break Canada’s cycle of false starts on adaptation and make the NAS commitment on municipal flood and wildfire protection a success.

Dr. Blair Feltmate is the Head of the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo.

[This article appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of ReNew Canada.]

Featured image: (Getty Images)