By Armando LaCivita

In April 2019, the Ontario government announced a historic $28.5-billion transportation plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe Region (GTHA), including four priority subway projects within Toronto. A few months later, the Getting Ontario Moving Act was enacted, granting ownership of the new subway projects to the province. Enter Metrolinx.

Metrolinx, a Crown agency of the Ontario government, is responsible for developing and operating an integrated transportation system for the GTHA. Metrolinx plans to deliver more than 40 new kilometres of subway lines, 50 kilometres of new LRT lines, and 200 kilometres of new GO train tracks. It will include 100 new stations and stops throughout the GTA, Hamilton, and Niagara Region.

Infrastructure Ontario, also a Crown agency, supports initiatives to modernize and maximize the value of public infrastructure and real estate, in cooperation with the private sector. Working together, Metrolinx and Infrastructure Ontario are developing new programs and processes to ensure the effective delivery of these complex transit projects. These projects involve complicated coordination among many stakeholders: everyone who has a cable, pipeline, or power line under the streets. How do you keep them all operating while you’re digging entrances and exits to the new subway lines without running into huge overhead costs?

Building transit faster

Paul Collins, utilities director of Capital Projects Group at Metrolinx and Gord Reynolds, vice president of Commercial Advisory & Strategy at Infrastructure Ontario, wanted to answer that question and find a way to deliver transit projects more quickly with fewer conflicts and delays. They proposed legislation that is the first of its kind in North America.

The Ontario government saw their bill, the Building Transit Faster Act (BTFA), pass very quickly in 2020, because MPs knew it would save both time and money on these huge projects. The legislation puts some backstops into negotiations with utilities, as it made it mandatory for the utilities to provide accurate data to the Crown agencies. This must be, as Reynolds says, “data that we’ve seen and located,” before design of the transit begins. And those designers are now required to use the same data. Contracts are fixed and immutable. No one can hold up the process by asking for more money to complete their information, their contribution to the project.

The legislation also empowered Metrolinx to access municipal rights of way. This would provide more certainty for the businesses affected and firm budgets for tax and ratepayers.

Collins and Reynolds developed Utility Conflict Management (UCM) practices to identify and resolve conflicts and the Office of Utility Coordination (OUC) to do the same with third-party utilities.

Collins wanted to prevent the usual situation where, as he says, “we are last to know and first to have to deliver.” A long-time advocate of knowing all the constraining parameters before any designs start and long before construction, he argues that “for every dollar spent on SUE (Subsurface Utility Engineering) investigation, you save six that you’d spend dealing with problems you find in the field.”

The confusions that slow things down are endless, ranging from the simple—two organizations using different words for the same thing—to the complex incompatible data. And confusions make a clear plan almost impossible. The former is partly solved by building in regular meetings to discuss hurdles, which encourages transparency and promotes reliability. They chose Esri’s geographic information system, ArcGIS, to address the latter.

Esri’s ArcGIS system played a critical role as it uses location to integrate different data types and sources from multiple organizations into a cohesive view that can be easily shared among stakeholders. As Brian Bell, director of utilities at Esri Canada says, “For large, multi-organization infrastructure builds, it is critical that asset and planning data is available through a centralized hub, unifying information access for multi-agency stakeholders through common views, supporting critical and complex decision-making.” Using ArcGIS, they can track, monitor and manage BTFA compliance requirements in one format. This provides the choir with one hymn book, one system of record shared among multiple asset owners and involved parties.

What legacy maps and spreadsheets depict as “in the ground” (what we think is there) versus what is “seen and located” (can be verified to be there) is, according to Collins, the single biggest challenge for this project.

Inconsistent data is annoying and makes for serious delays and confusion. Information that is siloed and unshared is problematic. But the worst problem when preparing for the huge upheaval of utility, wastewater, telecommunicatons, and similar essential services infrastructure that run underground, is not knowing exactly where they are, and the follow-up concerns that raises. Can they be moved, and if not, how can they be circumvented? As Reynolds puts it: “You can’t connect the dots if you don’t see the dots.”

To make sure it all worked as planned, they decided to run a pilot project on one of Infrastructure Ontario’s Subway Program projects—the Ontario Line.

Utility coordination

The first study they did was a SUE one. This tells them not only where things are, but importantly, what they’re made of and how old they are—all of which impacts if, and how, they can be moved. Armed with accurate data, Metrolinx and Infrastructure Ontario went to the owners of the pipeline and the telecommunications system and talked to them in a collaborative manner.

“Those companies are primarily concerned with their customers but with this information, we can ask intelligent questions and they can see that we want to be good partners,” says Collins. The company is forced by the BTFA legislation to cooperate, but “we want to use the carrot rather than the stick.”

Because not all the stakeholders have up-to-date maps of their assets and even fewer are likely to be aware of the placement of other systems, Collins says “we help them understand that it’s in their best interests to be able to share this information.” The dedicated operational team, created by the OUC and run by Infrastructure Ontario to manage utility coordination, proved invaluable in this process.

“Much of the infrastructure in urban areas is quite old and the recordkeeping associated with those old assets is often questionable,” says Bell. “Utilities aspire to meet modern customer needs and develop digital twins that enable them to operate more efficiently, and they see programs like these as helping them to move in the right direction.” As Reynolds adds, “We aren’t railroading utilities, we are just doing a better job of working with them, in a way that benefits Ontarians.”

One of the results of this pilot project is that companies involved now have accurate maps of exactly where their assets are—under the northern sidewalk, not the southern one—and those maps are held by the Crown agencies and will be constantly updated. This is the beginning of building a digital twin for these companies.

And of course, it benefits the city who also can use these maps. Now if they must dig, they will know where things are. This reduces that old routine of ripping up the road once and then watching some other group dig it up again six months later.

This ‘plan before you dig’ approach seems obvious now, but it’s a first—and it’s not limited to building subways. It’s scalable to smaller cities and can be used for any linear infrastructure build, like highways or even the broadband networks being built seemingly everywhere in Canada.

In March 2021, the Ontario government passed the Build Broadband Faster Act. By forcing preplanning on all the stakeholders, limiting the cost, and ensuring the collated data is accurate using Esri’s ArcGIS system, it’s now cheaper and more efficient to build broadband in Ontario, including where it is most needed: remote communities.

[This article originally appeared in the May/June 2022 edition of ReNew Canada.]

Armando LaCivita is district manager of the Ontario Region for Esri Canada.

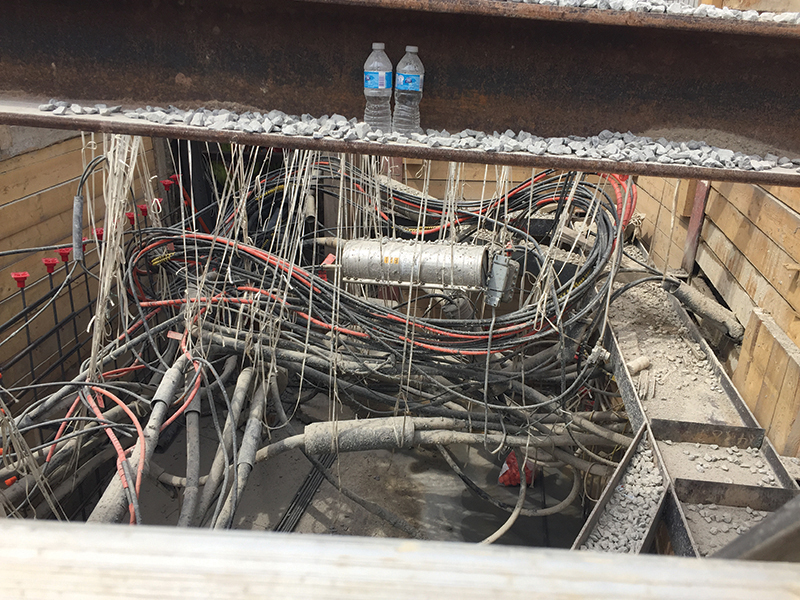

Featured image: Esri Canada was involved in a pilot project with Metrolinx and Infrastructure Ontario that helped manage and resolve conflicts around utility coordination. Metrolinx plans to deliver more than 50 kilometres of new LRT lines, including the Eglinton Crosstown West Extension. (Metrolinx)