Long-term efforts to build sustainable city-regions are rooted in attempts to slow down sprawl by building more compact communities that can be served effectively by transit.

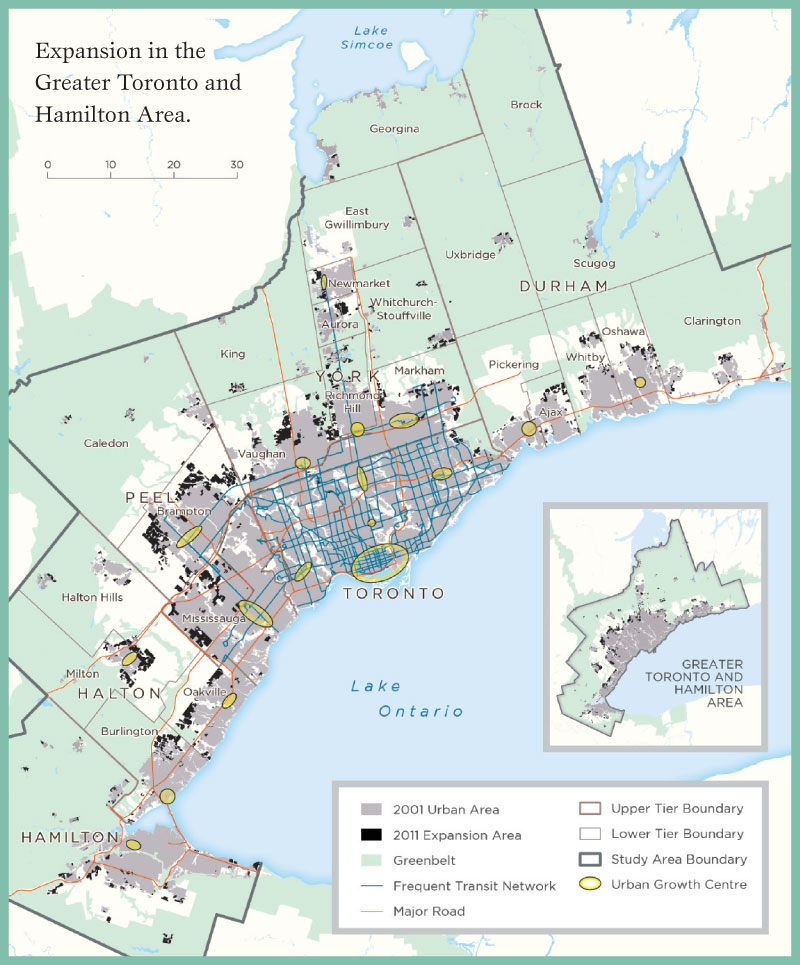

Two of Canada’s largest and fastest-growing city-regions—Metro Vancouver and the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA)—have ambitious long-term plans that aim to do exactly that. Both share similar planning goals and have used similar policy mechanisms to combat sprawl, achieve a more compact form, and focus transit-oriented development around urban centres. These two city-regions differ, however, in the timing of their plans and their approach to implementation and monitoring. Together they make an interesting case for comparison.

A 2010 Neptis report first compared the growth patterns of these two city-regions between 1991 and 2001, and recently released research extends the study period to 2011. This comparison of how the two regions have grown over a 20-year period is timely as both jurisdictions are reviewing their respective land use and transportation plans.

Metro Vancouver had a head start on growth management relative to the GTHA. Starting in the 1970s, British Columbia put in place strong protections for agricultural land with its Agricultural Land Reserve. But it is a consistent and long-standing approach to urban containment—to prevent growth from spilling into the countryside—that has produced results, including a reduction in the amount of land used for urban expansion and a greater diversity of housing stock. In recent years, Metro Vancouver has taken a more strategic approach to growth management, directing intensification to frequent transit corridors and urban centres.

Ontario’s growth management effort began in 2006, and like British Columbia, it has strong protections for agricultural land in southern Ontario. However, its plan takes a more generalized approach to intensification: 40 per cent of new residential development is directed to the already urbanized area. In addition, a complementary greenfield target was introduced that was meant to increase densities in new development at the

urban edge.

As the findings show, growth in the GTHA is still tilted toward greenfield development. Ontario could learn from Metro Vancouver by introducing a more strategic approach to growth that directs more new residents to areas with frequent transit service.

Growth at a glance

The GTHA experienced a tremendous amount of growth in the past 10 years (2001 to 2011), accommodating more than one million people and adding more than 450,000 new dwellings. In this decade, growth was achieved by using land more efficiently than was the case in the 1990s. Neptis findings show that the market more than policy was responsible for this shift to higher-density greenfield development.

In the Vancouver region, growth continued but slowed down between 2001 and 2011. Metro Vancouver maintained its goal of developing as a compact region by increasing its urban footprint by only four per cent and directing 75 per cent of new dwellings to the existing urban area.

Differences in growth

Three important differences in the way growth has been accommodated in the Vancouver and Toronto regions offer a reality check and possible guidance for the regions’ policy reviews at this critical juncture.

1. The GTHA is losing population in some established urban areas while growing mostly through greenfield development; Metro Vancouver is intensifying.

Between 2001 and 2011, Metro Vancouver continued to accommodate most population growth through intensification while the GTHA continued to accommodate the majority of new population growth through greenfield development.

- Despite a condo boom in parts of downtown Toronto and in the GTHA as a whole, only 14 per cent of net new residents were accommodated through the intensification of existing urban areas. In other words, 86 per cent of the net new residents added between 2001 and 2011 were housed in new suburban subdivisions built on greenfield sites.

- By contrast, in Metro Vancouver, 69 per cent of net new residents were accommodated in existing urban areas through intensification in the same period.

- In both city-regions, intensification accommodated a greater number of dwellings than people; 46 per cent of net new dwellings were accommodated in the existing urban area of the GTHA and 76 per cent of net new dwellings were accommodated in the existing area of Metro Vancouver. The gap between people and dwellings is like a result of declining household sizes across Canada and the increase in one-person households.

The research also found that new greenfield development in the GTHA was being built at higher densities than in the 1990s, as the rate of urban expansion slowed down while the rate of population increase stayed the same. Between 1991 and 2001, the urban area of the GTHA grew by 26 per cent; it grew by only 10 per cent between 2001 and 2011. One definition of urban sprawl is that the increase in urban expansion is greater than the increase in population. By this measure, the GTHA is no longer sprawling.

2. Growth in the GTHA is going to areas without transit; Metro Vancouver is achieving transit-oriented development.

The analysis of population and dwelling growth within walking distance of frequent transit corridors and stations shows:

- Very little of the GTHA’s population growth was located near frequent transit corridors or near GO train stations. Only 18 per cent of the region’s net new residents were accommodated near frequent transit routes, and only 10 per cent of net new residents were accommodated within 1,000 metres of a GO station.

- In Metro Vancouver, almost 50 per cent of the region’s net new population was accommodated near a frequent transit route, and 23 per cent of new residents were accommodated within 800 metres of a SkyTrain Station.

Although the plans for both city-regions contain transit-oriented development policies, only Metro Vancouver’s regional growth strategy directly integrates with its long-range regional transportation plan. An example is the adoption of the Frequent Transit Development Area policy in the 2011 strategy, which directs growth to corridors that are or will be served by frequent transit, as defined by TransLink, Metro Vancouver’s regional transit agency.

In the GTHA, land use planning and transportation planning appear to be on separate tracks. Municipalities began planning in conformity with the Growth Plan in 2006, two years before the release of The Big Move, the regional, Metrolinx-led transportation plan. As a result, there was less focus on accommodating growth around corridors and centres with existing or planned frequent transit service.

3. The GTHA offers a limited range of housing choices; Metro Vancouver has created a more balanced housing stock over the past 20 years.

In the GTHA, between 2001 and 2011, almost 86 per cent of net new residents were accommodated in dwellings built on greenfields. Most were single detached houses (62 per cent). In fact, over a 20-year period, the proportional composition of the GTHA’s housing stock has remained unchanged. In Metro Vancouver, by comparison, the housing stock has been transformed from one dominated by single detached homes to a more balanced stock offering residents a greater choice of housing types across the region.

Housing affordability is a problem in both regions. However, increasing the range of housing options is an important component of any policy to address housing price increases.

Implications for policy

Three policy lessons arise from the study of the two city-regions.

1. A hard urban boundary and a clear regional structure can support growth management.

In Metro Vancouver, a defined Urban Containment Boundary acts as a brake on outward development. Within that boundary, growth is targeted to urban centres, which are organized into a hierarchy according to their regional and local roles, and to areas served by the frequent

transit network.

Ontario’s Greater Golden Horseshoe has no such hard boundary. Instead, there is a requirement for 40 per cent of housing development to go to built-up areas and for greenfield development to be built at a certain density within an Urban Settlement Area. The settlement area is not delineated in the Growth Plan itself and is therefore not a hard edge.

2. Planning for land use and for transportation should be coordinated.

Both regions have transit-oriented development policies, but only Metro Vancouver’s regional growth strategy directly integrates with its long-range regional transportation plan.

In the Toronto region, there is a lack of integration between the Growth Plan and The Big Move, partly because the creation of a regional transportation agency and a long-range transportation plan came after the introduction of the Growth Plan. Neither plan attempts to direct a certain percentage of growth to particular transit-accessible locations across the region.

3. Support for regional growth management calls for cooperation and monitoring.

Metro Vancouver is a regional body that coordinates services across municipalities in the Vancouver region. It acts as a convener of local stakeholders and municipalities, all of which have to buy into the regional growth strategy. The role of convener is important in the success of the strategy, to ensure that local interests do not trump the regional perspective.

The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe does not have a similar structure for reconciling the needs of individual municipalities and the region as a whole. Individual municipalities carry out implementation and there is no requirement that these municipalities work together or consider regional priorities in their decisions.

Metro Vancouver also has a well-established monitoring program that tracks 55 indicators relating to land use, the environment, and the economy. In the Greater Golden Horseshoe, the Ontario Growth Secretariat has only recently established 14 indicators to monitor the effectiveness of the Growth Plan. Although the monitoring program for the Greater Golden Horseshoe is too new to have produced results, it is starting from a less robust foundation.

Trends and insights

This comparison between the two city-regions of Toronto and Vancouver offers insights not only into housing trends and development patterns, but also into growth management efforts in the two jurisdictions.

The Vancouver city-region has seen positive results from its early growth management efforts—but it is not resting on its laurels. Metro Vancouver has kept its plans up to date, revising them in response to emerging trends and pressures. In 2011, at the end of the study period analyzed in this paper, Metro Vancouver once again refined its plans into the regional growth strategy.

This document and its policies are appropriately named, since they are strategic, rather than generalized. The Urban Containment Boundary acts as a brake on outward development, but within that boundary, growth is targeted to urban centres, which are organized into a hierarchy according to regional and local roles, and to areas served by frequent transit networks.

In contrast, the Province of Ontario introduced its Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe in 2006, and even in 2015, the required elements of the plan are not fully in place everywhere in the region, as many municipal implementation efforts have been subject to Ontario Municipal Board appeals. The Growth Plan is very different from Metro Vancouver’s regional growth strategy, but it resembles some of British Columbia’s earlier efforts at growth management, with generalized intensification and greenfield development targets, applied broadly across the region.

The Growth Plan in its current form remains focused on the problems of the 20th century, not those of the 21st. For example, the plan is premised on the assumption that intensification—no matter where it is located inside the boundary of the urbanized area—will result in smarter growth, with the attendant benefits of reduced congestion, the efficient use of infrastructure, and more sustainable communities. This research shows, however, that generalized intensification alone may not achieve these goals, especially in the context of declining household sizes.

Instead, the changing geographies of growth and demographics in the GTHA are resulting in higher densities in new developments at the urban edge while many older, more central urban areas have declining populations. Although downtown Toronto has experienced significant population growth, that growth represents only five per cent of the GTHA’s population growth between 2001 and 2011.

A reality check

Given the “reality check” provided by this research, is it possible for the Province of Ontario to take a more strategic approach to growth management in the GTHA? The question will be answered during 2015 and 2016 as the province conducts its 10-year review of the Growth Plan and The Big Move.

Unfortunately, the Growth Plan, as it is currently formulated, “locks in” both population and employment projections, as well as the land budgets through which municipalities turn these projections into estimates of the amount of land needed for new development. Once land is designated for urban development, it seems it cannot be undesignated. Emulating Vancouver’s more strategic policies of focusing on the location of growth in proximity to areas with frequent transit more than simply the amount of new urban land necessary to accommodate growth would require a change in provincial policy.

The GTHA also lacks the supportive structure of Metro Vancouver. This body regularly convenes elected representatives from municipalities throughout the Vancouver city-region to deal with matters such as extensions to urban boundaries and discrepancies between regional and local perspectives. The GTHA has no formal convening body that requires elected representatives of the upper- and single-tier municipalities to think and act as a region; municipalities tend to act in isolation from one another rather than working cooperatively to shape the future of the GTHA.

The GTHA could learn from Metro Vancouver’s experience in linking transportation planning and land use planning. TransLink certainly plays a more direct role in planning the Vancouver region than its corresponding regional agency in the GTHA, Metrolinx. The Province of Ontario is preparing to spend billions of dollars on regional express rail, but these plans are not yet strongly or clearly linked to plans for targeted intensification. More strategic planning of growth will be necessary if the GTHA is to evolve into a polycentric region with concentrated employment and residential nodes across the region that facilitate more efficient use of the region’s transit network.

The review of Metrolinx’s regional transportation plan, The Big Move, is occurring at the same time, but on a separate track from the review of the Growth Plan. It is unclear how the outcome of one review will inform the other. In the Vancouver region, the roles and responsibilities of Metro Vancouver, municipalities, and TransLink are clearly articulated in the regional growth strategy. To date, Ontario’s Growth Plan leaves many aspects of its implementation ambiguous, which has led to appeals and related delays in its implementation. It will be necessary to address this gap in the review of both plans.

Although the Toronto and Vancouver regions face growth-planning challenges, both regions are successfully attracting new residents and employment. They frequently appear on lists of the most livable cities in the world. But with success come challenges that policy has been slow to address. New problems have emerged: smaller households, older households, emptying neighbourhoods, unused infrastructure in some places, and overused infrastructure in others. It is time for planning policy to evolve to address the growing pains of fast-growing city-regions. As an often-quoted saying has it: The future is not what it used to be.

Marcy Burchfield is the executive director of the Neptis Foundation, an independent foundation that conducts nonpartisan research on Canadian urban regions. Anna Kramer, as a researcher at Neptis, has analyzed spatial patterns of residential growth in four Canadian cities to update the original Growing Cities report. She currently works at Metrolinx, analyzing the social equity impacts of transit projects.