Canada’s First Nations communities are forging new partnerships to build infrastructure.

By John Tenpenny

Many of Canada’s Indigenous communities are in need of new infrastructure, from water assets and better roads to stronger schools and clean energy.

New partnerships between First Nations communities and asset developers are leading to some of Canada’s most incredible assets, assets that can be maintained by the communities they serve. This ability for the community to work on infrastructure assets, both in the short-term and long-term, is key for economic development.

How do we use these recent successes to encourage more asset development in remote communities? And how do we ensure capital is available for these projects to move forward in a timely fashion?

During a recent INFRAIntelligence webinar, with support from Sanexen, ReNew Canada explored Indigenous megaprojects and the infrastructure gap facing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. Panelists discussed some of the initiatives being spearheaded by governments and First Nations to strengthen economies in Indigenous communities.

Major projects coalition

According to Sharleen Gale, chief of B.C.’s Fort Nelson First Nation, being involved in major infrastructure projects is increasingly important to Indigenous communities.

“Overall, there is a want from our Nations to become involved as partners in the economic activity that is happening in their territories and our participation in major infrastructure projects is an opportunity for us to help shape the future and strengthen our economies.”

Stephen Lidington, with Colliers Project Leaders’ infrastructure advisory practice, agrees.

“Meaningful equity stakes for First Nations in projects enables First Nations participation in the economic mainstream and develops future opportunities.”

As chair of the First Nations Major Project Coalition (FNMPC), Gale has had a front row seat as the organization has advanced Indigenous communities’ shared interest in gaining ownership of the major projects taking place in its territories, including in her own backyard.

“Our nation is championing the Clarke Lake Geothermal Project, which represents a $100 million investment in the clean energy future of our territory,” says Gale of the project that is scheduled to come online in 2024.

Being developed in the existing Clarke Lake gas field in British Columbia, the Clarke Lake project will use the mid-grade geothermal heat resources in its reservoir to reduce emissions by displacing fossil fuels, while also demonstrating the value of geothermal energy as a viable clean energy technology for rural, Indigenous, and northern communities.

The FNMPC currently has five projects in various stages of planning and development in its portfolio with a potential investment value of $7 billion, including a group of 12 communities in Northern B.C. that have made the decision to acquire equity in the Coastal GasLink Pipeline. Gale adds that there is also interest from other Indigenous communities in participating in the Trans Mountain Pipeline project.

“What we’re seeing is that the business readiness of our First Nations is increasing and we’re moving beyond the traditional agreements to ownership and co-development.”

Priority lending

Lending a hand is the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB), which recently announced the launch of the Indigenous Community Infrastructure Initiative (ICII), which will enable the building of new infrastructure projects in Indigenous communities.

As part of the ICII, the CIB will tailor its low-interest and long-term financing to provide loans of $5 million, and up, for up to 80 per cent of total project capital cost.

According to Hilary Thatcher, CIB’s senior director, project development for Indigenous infrastructure, the CIB was set up to attract and co-invest with private sector and institutional investors in five key priority areas—green infrastructure, clean power, broadband, public transit, trade and transportation.

“And these are all areas where many First Nations are seeking investments, either in large-scale projects where they can be a meaningful partner or in projects that are going to directly impact their communities and help build and grow their community-based infrastructure.”

The program was developed with input from Indigenous leaders, communities, and infrastructure organizations, says Thatcher.

“Projects are being driven by communities that are growing in their financial and development capacity and understanding of how to forge strong partnerships and are looking for strong private sector partners to help see these projects through to fruition.”

Others who are active in projects focused on infrastructure in the five key priority areas involving CIB Indigenous partners include the Oneida Energy Storage project in Ontario and the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link, which involves the construction of a new 1,200-kilometre, 150-megawatt transmission line between Nunavut and Manitoba.

Barriers to progress

Most Indigenous communities have limited capital, says Gale, which means down payments on projects must be financed.

“Access to competitively-priced equity capital is a major challenge.”

Becoming a partner is time consuming and capital intensive, says Lidington.

“It requires a tremendous amount of effort to be a credible and bona fide counterparty in these megaprojects, which is not inexpensive due to the amount of commercial, financial, and legal due diligence.

“And not many Indigenous communities have the capital to cover those development costs.”

Lidington and Gale both point to the important role the FNMPC plays in helping Indigenous communities navigate the capital markets and become partners in major projects.

But there is still much to be done.

“In one case when we sourced commercial capital for a project, we were told that it would be between 12 and 15 per cent when the rate of return of the project was going to be nine per cent,” explains Gale. “So, in that case, our member had to give up their equity interest in the project because they couldn’t find alternatives.”

First Nations have been advocating to the federal government to step in and help communities get across the finish line with access to capital, she adds. “We need that, either through loan guarantees or equity loan guarantees.”

To be clear says Gale, First Nations are not looking for handouts; rather, they are looking for help on commercial terms that enable them to enter into the economic mainstream in a big way.

“We see these projects happening around us and we want to be part of them,” she says.

At the recent First Nations Major Projects Coalition Indigenous Sustainable Investment Conference, FNMPC executive director Niilo Edwards called for a national strategy for Indigenous access to capital.

“For a lot of First Nations there isn’t a lot of risk capital around to stimulate a good return from money borrowed in the commercial markets, without some kind of credit enhancement or financing innovation from government. In Ontario, in Alberta, you have loan guarantee programs at the provincial level, which have proven successful. A national strategy is something that needs to be paid close attention to by the federal government if we’re going to have true inclusion of Indigenous people in the economy.”

Budget benefits

In its Budget 2021, the federal government announced funding to help close infrastructure gaps in Indigenous communities. As part of an $18 billion package, the government promised $6 billion over five years to support infrastructure, including support for immediate demands, as prioritized by Indigenous partners, with shovel-ready infrastructure projects.

While recognizing that the need for funding is tremendous and that the federal government announcement will benefit First Nations communities, Gale believes that the work the FNMPC is engaged in is just as important.

“It’s a huge step in the right direction, but the coalition is focusing on ensuring our members get involved in equity positions and ownership and co-development of major projects.

“We know that the government isn’t always going to be there to help us with our funding needs and so we feel that the only way to be involved is to be part of these major projects as owners so we can bring our own revenue streams and use those funds to build the type of projects that raise the standards of living for our community members.”

Early engagement

Putting the communities in the forefront, and taking into account what is important to them, even before a project is conceived, is important. As is having a clear idea of what the priorities and benefits are for the affected Indigenous community at the end of the project.

“What I’m hearing from Indigenous communities, and in my experience with those communities, is they want to be engaged in discussions of projects from the early development stage,” says Thatcher.

“No one knows the land better and it can save the project not only delays and costs but can save the project in terms of its reputation and its stake with a potential future Indigenous partner.”

Early engagement with First Nations is critical, agrees Gale.

“We’ve had people come to us with preconceived plans and we’ve had to tell them that the project can’t be built where they wanted it.

“Had they come to us earlier and invited us to be part of the project, whether we wanted to be an equity partner or just wanted to ensure that the project they were building was going to be in line with our values, then we could have helped either way.”

Taking a community’s needs into account is the basis of a development plan known as La Grande Alliance—a $4.7 billion dollar infrastructure agreement signed in February 2020 between the Cree Nation government and the province of Quebec.

It proposes road extensions and upgrades, a 700-kilometre railway to the far northern reaches of Cree territory, a deep seaport, new power lines and the creation of a network of protected areas, among other infrastructure projects to be built in three stages over the next 30 years.

Earlier this year, a $4.4 million contract was awarded for the phase one feasibility study that also marked the start of a 12-month process aimed at involving stakeholders in the co-design of the plan that could transform Cree territory.

Continued efforts are required to work directly with First Nations in meaningful and collaborative ways that will lead to much-needed investments in better infrastructure and sustainable economic growth.

“It’s important that Canadians understand that we want our communities to look like communities,” says Gale. “We want beautiful homes, we want roads, we want fresh drinking water. These are all things that some of us have and some of us desire and we all have to work together so that we’re raising the living standards for our people.”

John Tenpenny is the editor of ReNew Canada.

[This article originally appeared in the September/October edition of ReNew Canada.]

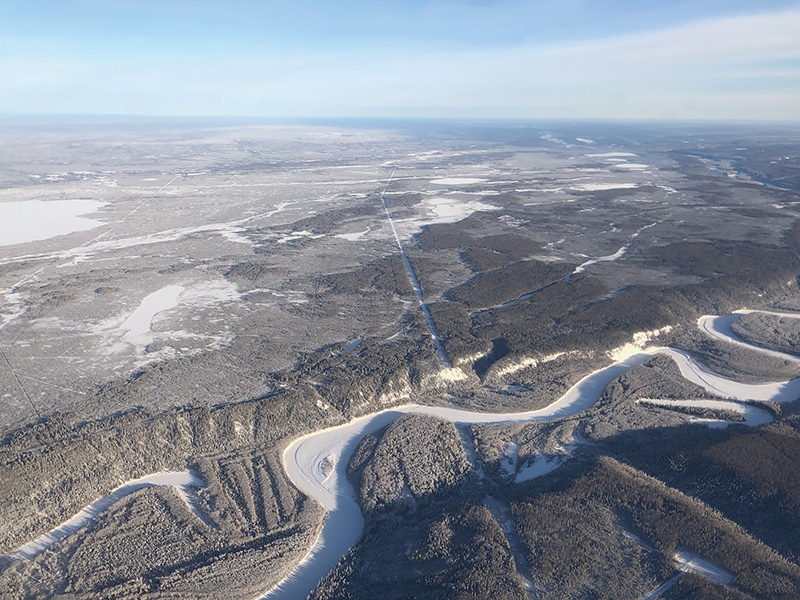

Featured image: The Keeyask Generation Project is a partnership between Manitoba Hydro and four partner First Nations. (Manitoba Hydro)