Toronto is a city with more buildings of 12 storeys or higher than any other in North America save New York, and it is experiencing a second wave of high-rise construction. A January 2014 report by the Consumers Council of Canada is jumpstarting a discussion around the effect of residential intensification on cities and consumers.

In the study, Residential Intensification: Density and its Discontents, housing economist Will Dunning points out that in Canada’s three largest urban centres—Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal—almost 700,000 households (15 per cent of the total) already live in condominiums. Between 2006 and 2011, new condos represented 38 per cent of all new living spaces in the three markets, compared to more than 20 per cent in Canada as a whole. In the next two decades, according to Dunning’s projections, these three markets will require between 26,000 and 32,000 new condominiums units per year. This would represent between 43 to 53 per cent of all new housing in those areas, amounting to between 14 and 18 per cent of all new housing in Canada.

This raises concerns beyond the sheer volume of expected development: building height, proximity to low-rise neighbourhoods, shrinking unit size, the prevalence of glass buildings, and suspicion of rampant speculative activity creates concern among consumers and residents.

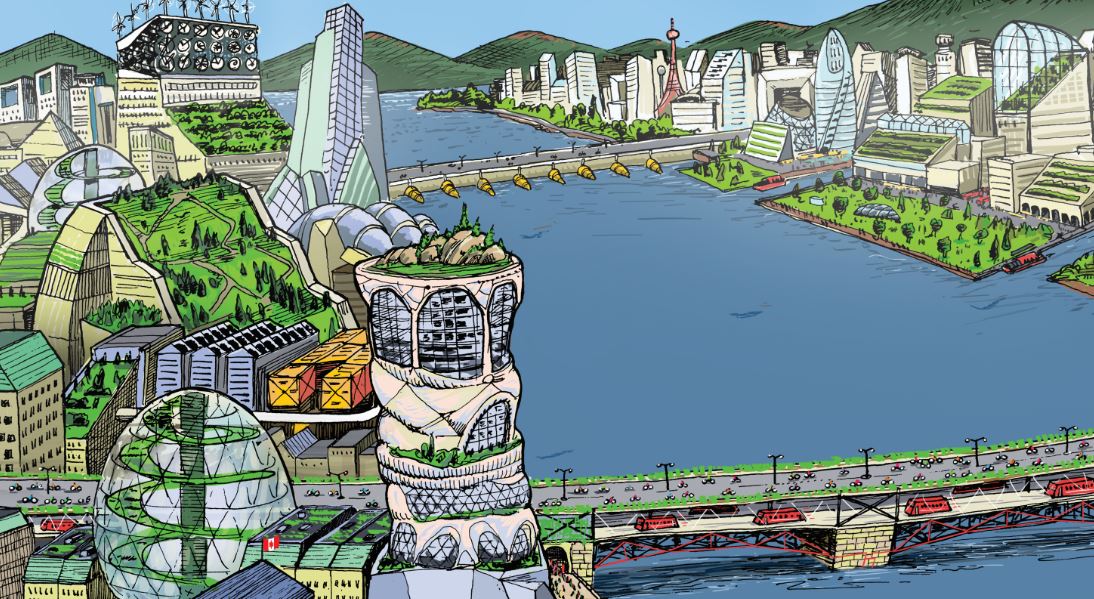

“Combine this with debates about congestion, transit, and infrastructure, and housing intensification becomes part of a much larger conversation about city living and city building,” the report states. “Left unaddressed, these concerns could also result in the creation of high-rise ghettos, development without neighbourhood context, tall building energy hogs, over-taxed infrastructure, and condo owners stuck in possession of stranded diminishing assets.”